- Author Matthew Elmers elmers@military-review.com.

- Public 2023-12-16 21:49.

- Last modified 2025-01-24 09:17.

Real knightly armor of the Renaissance. Today we will get to know them in the most detailed way!

“If I had not been wearing impenetrable armor, this villain would have shot me seven times as coldly as a hardened deer. It hit every seam of my shell with a longest arrow. If I did not wear Spanish chain mail under the shell, I would be uncomfortable."

"Ivanhoe" Walter Scott

Museum collections of knightly armor and weapons. Today, personally, I have, let's say, a small holiday, which, I hope, will be a bit of a holiday for lovers of antiquity in VO. And it is connected with the fact that we are starting a new series "for life", which will be devoted to individual collections of knightly armor and weapons in museums in different countries. That is, it will be a story about the museum itself, where these items are exhibited, and about those exhibits that will be presented in the text as illustrations. No wonder it is said that there is nothing more interesting … useless knowledge, because you usually rest on it. So here it will be told about the piles of completely useless, but remarkably beautiful ancient iron. And I promise that all the photos shown here will be … very nice to look at. Well, then, what if one of us gets rich enough that he wants to decorate his house with real knightly armor - so there will be something for him to be guided by. And who knows, or rather, who knows his life path - maybe this will happen someday …

Well, let's start with the wonderful collection of the Wallace family's armor, which is usually called the "Wallace Collection" in Russia. It is located in a three-story mansion on Manchester Square in central London in the Westminster administrative district. And it was opened to visitors back in 1900, that is, it is already 121 years old, and all this time its treasures never cease to please the eye. It was collected by four generations of the Wallace family between 1760 and 1880 and today it consists of about 5,500 objects of both fine and decorative arts of the 14th-19th centuries, a collection of paintings from the 18th century … Louis XV furniture, European and Oriental weapons and armor, Sevres porcelain, many canvases of various master painters - from Titian, Rembrandt and Rubens to Antoine Watteau and Nicolas Lancre. Moreover, you can visit the "Collection" completely free of charge, such was the will of the testators, who provided the collection to the full ownership of the state. Her treasures are displayed in 25 galleries. But today, since we have a military site, we will visit only one: weapons and armor.

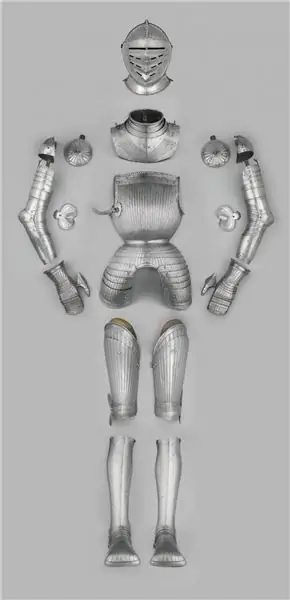

The customer wanted to get a unique armor, but so that it was no worse than others, and the master, of course, tried to please him. This armor, with its exquisite abundance of corrugated surfaces, is the finest of a number of samples of the "Maximilian style" in the Wallace collection. By the way, we recall that this style was born not without the participation of the German Emperor Maximilian I (1459-1519), who was both a wonderful knight and the greatest patron of the German Renaissance.

In the articles here on VO it was already said that over time, the armor became so expensive that even kings could not afford to order 2-3 armor - one for ceremonial exits, another for combat, and the third for tournaments. So, more economical, let's say, "headsets" appeared, that is, sets of parts that made it possible, without altering the armor itself, to quickly change its functionality.

How to distinguish - is it combat armor or ceremonial? It's very easy. On the combat shell on the left (or right, depending on where to look) there was always a lance hook or stop, which made it possible to hold a heavy spear in his hands. This piece of armor is complex and can be folded.

No wonder Kohlman Helmschmid is considered one of the greatest gunsmiths of all time, he created such elegant armor - downright clothes of polished metal. For generations, the Helmschmids were the court armourers of the Habsburg emperors, the most powerful aristocratic dynasty in European history. Their work can always be distinguished by the combination of technical excellence with the highest quality engraved and gilded decor.

Not only knights wore armor at this time, but also landsknechts - hired soldiers from the German principalities. Their life was harsh, their morals were rough and cruel, and therefore they dressed provocatively, in the style of "lush and cut": clothes, distinguished by the elaboration of cuts and tears received in battle, so that you can see the landsknecht (and understand who is in front of you!) could be from afar. But, as in the case of sailors and prisoners who covered their bodies with tattoos, the fashion for which even penetrated the royal palaces, the clothes of the landsknechts, in fact, the dregs of society, became popular in high society.

So, even armor (!) With a complex and thoughtful decor, created by a combination of chasing, etching and gilding, began to be ordered "for the landsknecht". So this armor, and quite military, was made, most likely, for a nobleman, the commander of the professional infantry of the Landsknechts.

It is believed that they belonged to Alfonso II, Duke of Ferrara, Modena, Reggio and Chiaxtres [Chartres], Prince Carpi, Count Rovigo, Lord Kommachio, Garfagnana, etc. Piccinino does not have signatures on them, but they are very similar to the armor made by him for the Duke of Parma, who are in Vienna. There is armor of his work in other museums, including our Hermitage.

Usually readers of articles "about knights" constantly ask questions about how much that weighs in a knight's armor. Well - the Wallace collection has done a similar study of one of their most beautiful Renaissance armor, by Pompeo della Cesa (c. 1537-1610) from Milan, c. 1590 (c) Wallace Council of Trustees, London

If we consider armor not only as a weapon, but also as a system of signs, which, however, has always been clothing, then the most … important message that the armor of the Renaissance contains is strength and beauty. Polished surfaces reflect sunlight, and therefore the armor directly radiates "divine power" bestowed by God himself on the knighthood.

Well, this power was demonstrated not only on the battlefield, but also in exquisite battles - knightly tournaments. Moreover, tournament armor was very different from combat. Or, additional details were made for the combat ones, which turned them into tournament ones. So the cuirass of this armor has two-layer reinforcement; it can be hit right at the gallop with a long heavy spear without injuring the owner.

The breastplate is signed by the manufacturer POMPEO, which is a rare example of a gunsmith's signature.

Another way in which the European aristocracy reinforced the idea of superiority was to establish connections between themselves and the heroes of ancient mythology and pseudo-history. For example, many Italian Renaissance families claimed descent from classical figures such as Hector, Achilles, and Hercules. In other parts of Europe, false family lines have been invented, dating back even to characters from the Old Testament.

As the Renaissance fascination with everything related to the Ancient World spread throughout Europe, artists quickly developed an intricate language of appropriate iconography and design to visualize this modern communication with the distant past. For their part, the armourers developed an "antique or heroic" style based on a careful study of ancient Greek and Roman armor design, complemented by an admixture of their pure and sometimes completely unbridled imagination.

Not only that, the rulers of the Renaissance revived the Roman tradition of the triumphal entrance, the showy parade of a victorious army. For such events, fantastically ornate armor was created, such as this embossed and gilded helmet, adorned with leaves and the grinning face of a forest spirit.

Many renowned artists and designers, including Uccello, Botticelli, Durer, Burgkmayr, and Holbein, have collaborated with gunsmiths, designing jewelry designs for rich armor and even helping to create completely new and highly original styles.

By 1500, an incredible number of different metalworking methods had been developed, and all of them were applied to armor. Some of them were very ancient. Others are completely modern. For those years, of course.

Basic forms of armor could be enhanced by surface decoration. The acid etching process at the beginning of the 16th century was completely new and allowed for the first time to decorate hard carbon steel with what at first glance looks like an engraving. But it must be remembered that the mechanical engraving of hardened and tempered medium carbon steel armor, while not impossible, was extremely difficult and time consuming. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, engraving was usually done on strips of softer copper alloy or silver, which were then riveted to steel plates to form decorative borders. The invention of etching with aggressive chemicals in 1485 (apparently in Flanders) made it possible to cover armor surfaces with patterns anywhere and not limit their area.

The basic etching technique was to apply an acid-resistant coating called resist, based on wax or bitumen, onto the metal surface to be decorated. Then the alleged image was scratched on it to metal, which was then immersed in an acid or etchant. The drawing thus “gnawed” into the plate, without any expenditure of hard manual labor on the part of the master.

This concludes our visit for today, but we will continue it to look at a few more completely unique armor from this collection.

P. S. The author and the site administration express their deep gratitude to the Board of Trustees of the Wallace Meeting represented by the head of the communications department Kathryn Havelock for the opportunity to use materials and photographs from the collection's funds.