- Author Matthew Elmers elmers@military-review.com.

- Public 2023-12-16 21:49.

- Last modified 2025-01-24 09:17.

Both the sea and the mountains saw me in battle

with numerous knights of Turan.

What have I done - my star is my witness!

Rashid ad-Din. Jami 'at-tavarih

Contemporaries about the Mongols.

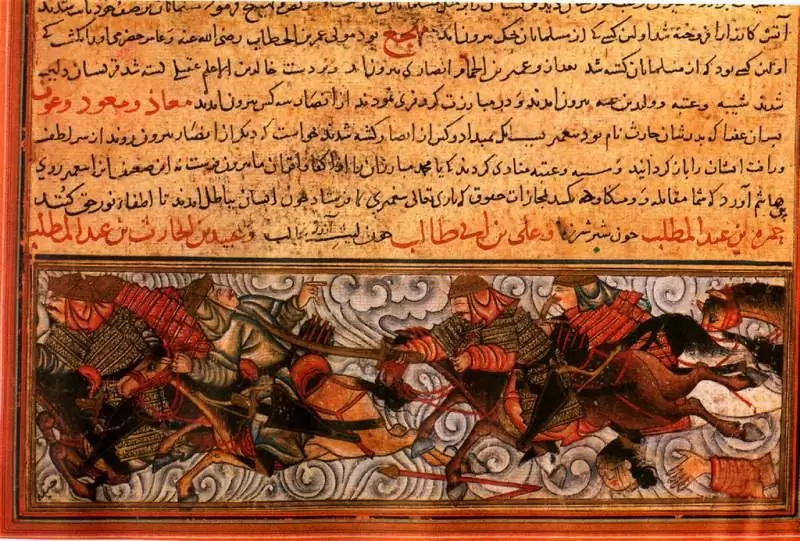

Among the many sources of information about the conquests of the Mongols, the Chinese occupy a special place. But it should be emphasized that there are a lot of them. There are Mongolian, Chinese, Arab, Persian, Armenian, Georgian, Byzantine (yes, there are some!), Serbian, Bulgarian, Polish sources. There are also burials in which characteristic arrowheads and other weapons are found. Penza Zolotarevka alone is worth what, how many have already been found here and continue to find …

Chinese sources report …

After the Persian sources, we turn to the Chinese sources. In theory, it should be the other way around, but Rashid ad-Din's book is already very well written, and besides, it came across to me first, that's why we started with it.

Sources of Chinese authors are also very interesting. And they not only can give their researcher very extensive material concerning the history of both the Chinese and Mongolian peoples, but they allow to clarify many information. In particular, the evidence of the same Persian and Arab chroniclers. That is, we are dealing with cross-references to one and the same event, which, of course, is very important for the historian. Today the value of Chinese sources containing information about Mongolia of the 13th century and other countries of the empire of Genghis Khan is generally recognized. Another thing is that our Russian researchers find it difficult to study it. You need to know Chinese and Uyghur languages, moreover, at that time, you need to have access to these sources, but what is there access - trivial money to live in China and be able to work with them. And the same goes for the possibility of working in the Vatican library. You need to know medieval Latin and … it's banal to have funds, pay for food and accommodation. And the open poverty of our learned historians simply does not allow all this. Therefore, one has to be content with earlier translations and what was done in a centralized manner by the historians of the USSR Academy of Sciences, as well as translations of European researchers in their own languages, which … you also need to know and know well!

In addition, if the works of Plano Carpini, Guillaume Rubruc and Marco Polo were published many times in various languages, then books in Chinese are practically inaccessible to the general mass of readers. That is - "they simply do not exist." That is why many people say that, they say, there are no sources on the history of the Mongols. Although they actually exist.

Let's start with the fact that the most ancient work known today, which is specifically dedicated to the Mongols, is "Men-da bei-lu" (or in translation "Full description of the Mongol-Tatars"). This is a note from the Ambassador of the Song Empire or Song Chao - a state in China that existed from 960 to 1279 and fell under the blows of the Mongols. And not just Song, but Southern Song - since the history of Song is divided into Northern and Southern periods associated with the transfer of the capital of the state from north to south, where it was moved after the conquest of northern China by the Jurchens in 1127. The southern Song first fought them, and then the Mongols, but was conquered by them by 1280.

Spy Ambassadors and Traveler Monks

In this note, Zhao Hong, the South Sung ambassador to North China, who was already under Mongol rule at that time, informs his superiors in detail about everything that he saw there and that had at least some significance. The note was drawn up in 1221. The presentation is clearly structured and divided into small chapters: "Founding of the state", "The beginning of the rise of the Tatar ruler", "Name of the dynasty and years of government", "Princes and princes", "Generals and honored officials", "Trusted ministers", "Military affairs "," Horse breeding "," Provision "," Military campaigns "," Position system "," Manners and customs "," Military equipment and weapons "," Ambassadors "," Sacrifices "," Women "," Feasts, dances and music". That is, we have before us the most real "spy report", in which its author described almost all aspects of the life of the Mongols. He also gives important information about Mukhali, the governor of Genghis Khan in North China and his immediate entourage. Among other things, from this message, we can learn that the Mongols on the ground widely attracted local cadres of Chinese officials and those … actively cooperated with the conquerors!

"Men-da bei-lu" was translated into Russian as early as 1859 by VP Vasiliev and was widely used by Russian historians who wrote about the Mongols. But today a new translation is needed, which would be devoid of the identified shortcomings.

The second valuable source is "Chang-chun zhen-ren si-yu ji" ("Note on the journey to the West of the righteous Chang-chun") or simply "Si-yu ji". This is the travel diary of the Taoist monk Qiu Chu-chi (1148-1227), who is better known as Chang-chun. It was led by one of his students, Li Chih-chan.

Discovered in 1791, it was first published in 1848. The diary contains observations on the life of the population of those countries that Chiang Chun visited with his students, including Mongolia.

"Hei-da shi-lue" ("Brief information about the black Tatars") - this source also represents travel notes, but only of two Chinese diplomats. One was called Peng Da-ya, the other Xu Ting. They were members of the diplomatic missions of the Southern Song State and visited Mongolia and the courtyard of Khan Ogedei. When Xu Ting returned back in 1237, he edited these travel notes, but in their original form they did not reach us, but came down to the edition of a certain Yal Tzu in 1557, published in 1908. The messages of these two travelers cover a wide range of issues, including the economic life of the Mongols, their appearance, the life of the nobility, and court etiquette. They also described a round-up hunt among the Mongols, noting that this was a good preparation for war. Xu Ting talks in great detail about the crafts of the Mongols and, which is quite understandable, the manning of the Mongolian troops, their weapons, describes their military tactics, that is, these so-called "ambassadors" not only performed their representative functions, but also collected intelligence information, and it must always be very accurate.

"Sheng-wu qin-zheng lu" ("Description of the personal campaigns of the sacred-warlike [emperor Chinggis]") is a source relating to the era of the reign of both Genghis Khan himself and Ogedei. It was discovered at the end of the 18th century, but due to the complexity of translation from the 13th century language, it was not paid much attention to for a long time. As a result, it was prepared for publication only in 1925 - 1926, and extensive comments were made to the translation. However, this source has not yet been fully translated into Russian and therefore has not been fully investigated!

The most important Mongolian source

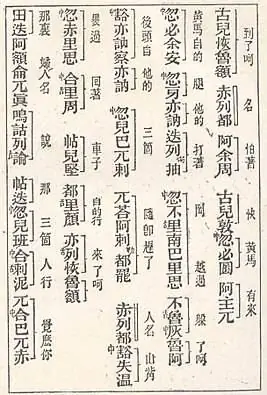

"Mongol-un niucha tobchan" ("The Secret Legend of the Mongols" - the most important source on the early history of the Mongols, the discovery of which was closely connected with Chinese historiography. Originally "Legend …" was written using the Uyghur alphabet, borrowed by the Mongols at the beginning of the 13th century., but it has come down to us in writing in Chinese characters and with an interlinear translation of all Mongolian words and an abbreviated translation of all its parts already in Chinese. This source is very interesting, but also very complex for a number of reasons. Suffice it to say that everything is discussed in it, from the question of authorship and the date of writing to the name itself. Controversy among specialists also raises the question of whether it is a complete work or is it only part of a larger volume of work, and whether it appeared before or after the death of Khan Udegei. So today, even the date of writing this document requires additional research with the involvement of all known Chinese and Korean, as well as Persian sources, which, of course, is only within the power of a large team of specialists with significant resources. The content of this very monument gives reason to believe that it was written (or recorded) in the form of a story by one of the old nukers of Genghis Khan, made in the year of "Mouse" (according to the Mongolian calendar) during the kurultai on the river. Kerulen. Moreover, for some reason this kurultai was not recorded in official sources. Interestingly, this indirectly indicates its authenticity. Since all the dates of the kurultays are known, the easiest way would be, be it a fake, to tie it to one of them, which, however, was not done. But exact dating is perhaps the most important task of any forger, and why it is so clear without much reasoning. By the way, the translation by A. S. Kozin (1941) in Russian on the Internet …

In China, the Secret Legend of the Mongols remained for a long time as part of Yun-le da-dyan. It was an extensive compilation of 60 chapters in a table of contents and 22,877 chapters directly in the text of the writings of various ancient and medieval authors, which was compiled in Nanjing in 1403 - 1408. Many chapters of this work perished in Beijing in 1900 during the “boxer uprising”, but some copies of this document were acquired in 1872 and then translated into Russian by the Russian researcher in Sinology P. I. Kafarov. And in 1933 it was returned to China in the form of a photocopy from the original, which is now kept in our Eastern Department of the Gorky Scientific Library at Leningrad University. However, it was only after the Second World War that this document became widespread in the world scientific community. By the way, the first complete translation into English was made by Francis Woodman Cleaves only in 1982. However, in English the title of this source does not sound so lofty, but in a much more prosaic way - "The Secret History of the Mongols".

Legal documents

During the domination of the Mongols in China, a large number of purely legal documents were left, which today are combined into collections: "Da Yuan sheng-zheng goo-chao dian-zhang" - an abbreviated version of "Yuan dian-zhang" ("Establishments of the [dynasty] Yuan"), and "Tung-chji tiao-ge" - again two large compilations from many works. Their exact dating is unknown, but the first consists of documents from 1260 - 1320, and the second - appearing in 1321 - 1322. P. Kafarov got acquainted with "Yuan dian-chzhang" in 1872, but its photolithographic publication was carried out in China only in 1957. Accordingly, "Tung-chzhi tiao-ge" is a collection of Mongol laws dated 1323. It was published in China back in 1930. It is clear that such primary sources are very valuable material for all students of the era of Mongol rule in China.

This, perhaps, is worth dwelling on here, because just a listing of all other Chinese documents on the history of the Mongols, if not a monograph, then an article of such a large volume that it would be simply uninteresting to read it to non-specialists. But it is important that there are many, very many such sources - hundreds of thousands of pages over different years, which is confirmed by cross-references and the content of the texts themselves. However, these documents are very difficult to study. You need to know Chinese and not just Chinese, but Chinese of the 13th century, and preferably also the Uyghur language of the same time. And who today and for what money will be going to study all this in Russia, and most importantly - why! So insinuations about other Chinese sources, not to mention Mongolian ones, will continue in the future. After all, "she feeds on fables" …

References:

1. History of the East (in 6 volumes). T. II. East in the Middle Ages. Moscow, publishing company "Eastern Literature" RAS, 2002.

2. Khrapachevsky RP The military power of Genghis Khan. Moscow, Publishing house "AST", 2005.

3. Rossabi M. The Golden Age of the Mongol Empire. Saint Petersburg: Eurasia, 2009.

4. Chinese source about the first Mongol khans. A gravestone inscription on the grave of Yelui Chu-Tsai. Moscow: Nauka, 1965.

5. Cleaves, F. W., trans. The Secret History of the Mongols. Cambridge and London: Published for the Harvard-Yenching Institute by Harvard University Press, 1982.