- Author Matthew Elmers elmers@military-review.com.

- Public 2023-12-16 21:49.

- Last modified 2025-01-24 09:17.

Back in 1902, the Russian Marine Technical Committee reported in one of its reports: "Wireless telegraphy has the disadvantage that a telegram can be caught on any foreign radio station and, therefore, read, interrupted and confused by extraneous sources of electricity." Perhaps it was this statement that became for many years the quintessence of electronic warfare in all subsequent wars. In Russia, the pioneer of theoretical calculations concerning electronic warfare was in 1903 Alexander Stepanovich Popov, who formulated the main ideas of radio intelligence and warfare in his memo for the Ministry of War. However, the practical implementation of the idea of electronic warfare was received in the United States in 1901, when engineer John Rickard used his radio station to "clog" the information broadcasts of competing mass media. The whole story concerned the radio broadcast of the America's Cup yacht regatta, and Rickard himself worked for the American Wireless Telephone & Telegraph news agency, which wanted to keep the "exclusive rights" for broadcasting at any cost.

In a combat situation, radio countermeasures were first used in the Russo-Japanese War. Thus, in accordance with Order No. 27 of Vice Admiral S. O. Makarov, all forces of the fleet were instructed to observe strict radio discipline and to use all possibilities to detect enemy radio transmissions. The Japanese also worked in a similar way, carrying out the direction finding of the ship's radio stations with the determination of the distance to the source. In addition, interception of enemy messages began to enter into practice, however, it did not receive much distribution - there was an acute shortage of translators.

Vice-Admiral Stepan Osipovich Makarov

Radio communication in the full sense of the word was first implemented on April 2, 1904, when the Japanese once again began to fire at Port Arthur from heavy guns. The cruisers Kasuga and Nissin operated with their 254-mm and 203-mm calibers from a decent distance, hiding behind Cape Liaoteshan. Adjusting fire from such a range was problematic, so the Japanese equipped a couple of armored cruisers for visual control of the shelling. The observers were located at a comfortable distance from the coast and were inaccessible to the Russian artillery. Naturally, all adjustments for the main calibers "Kasuga" and "Nissin" were transmitted by radio. In this situation, the command of the Russian fleet equipped the squadron battleship Pobeda and the radio station on the Golden Mountain, which jointly interrupted the working frequencies of the Japanese. The tactics were so successful that not a single shell from Kasuga and Nissin did any tangible damage to Port Arthur. And the Japanese have released more than two hundred of them!

Squadron battleship Pobeda in Port Arthur. 1904 g.

In 1999, the Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation declared April 15 (April 2, old style) as the Day of the Electronic Warfare Specialist, which is still an official holiday. The advantage of the Russians in that episode was not only successful tactics of use, but also technical superiority over the Japanese. So, the Japanese fleet used rather primitive radio stations that were not able to change the frequency of operation, which greatly simplified their suppression. But in Russia they could boast of domestic high-class radio stations from the Kronstadt workshop for the manufacture of wireless telegraph devices, as well as Russian-French ones from Popov-Dukret-Tissot. There were also German Telefunken with English Marconi. This technique was powerful (over 2 kW), allowing the operating frequencies to be changed and even power to be changed to reduce the likelihood of detection. The Russians' top-level technology is the particularly powerful Telefunken radio station, which makes it possible to keep in touch at ranges exceeding 1,100 kilometers. It was installed on the basis of the cruiser "Ural", which is part of the 2nd Pacific squadron of Vice Admiral Zinovy Petrovich Rozhestvensky. A station of the same capacity No. 2 was installed in the Vladivostok fortress. Naturally, the 4.5-kilowatt "Telefunken" was a dual-use product - it was planned to use it to jam Japanese radio communications according to the "big spark" principle due to the much higher power of the radio signal. However, there was a serious danger of countermeasures from the Japanese fleet, which could track such a "super station" and open artillery fire at the source.

Auxiliary cruiser Ural . Tsushima Strait, 1905

Obviously, ZP Rozhestvensky thought about this when he forbade the captain of the Ural to jam the Japanese when approaching the Tsushima Strait on May 14, 1905. During the battle itself, the Russian ships partially used their capabilities in suppressing enemy radio communications, and after the battle, the remnants of the squadron during the retreat took the bearings of the Japanese ships in order to avoid unwanted contacts.

Gradually, radio suppression and direction finding skills became mandatory in the fleets of all major powers. The British and American navies tried new tactics during exercises back in 1902-1904. And the British in 1904 intercepted Russian radio messages and read their contents without hindrance. Fortunately, there were enough translators in the Admiralty.

Alexey Alekseevich Petrovsky

The second major theater of military operations where electronic warfare was used was, naturally, the First World War. Before the start of the conflict in Russia, Aleksei Alekseevich Petrovsky created a theoretical basis for substantiating the methods of creating radio interference, and also, importantly, he described methods of protecting radio communications from unauthorized interception. Petrovsky worked at the Naval Academy and was the head of the laboratory of the Radiotelegraph depot of the Naval Department. The theoretical calculations of the Russian engineer were practically tested in the Black Sea Fleet immediately before the start of WWI. According to their results, ship radiotelegraph operators were taught to get rid of enemy interference during radio communications. But it was not only in Russia that a similar branch of military affairs developed. In Austria-Hungary and France, since 1908, special forces have been operating to intercept the enemy's military and government communications. Such radio interception tools were used during the Bosnian crisis of 1908, as well as in the Italo-Turkish war of 1911. Moreover, in the latter case, the work of the Austrian special services made it possible to make strategic decisions regarding countering possible Italian intervention. At the forefront of electronic warfare in those days was Britain, which throughout the First World War read the encryption of the Germans, filling their hand before the famous Operation Ultra of the Second World War.

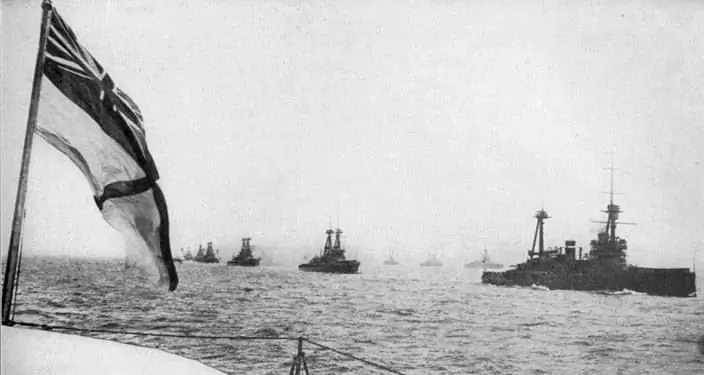

British Pride - Grand Fleet

In August 1914, the Admiralty organized a special "Room 40", whose employees were engaged in radio interception on the equipment "Marconi", developed specifically for this structure. And in 1915, the British deployed a wide network of intercept stations "Y stations", engaged in listening to German ships. And it was quite successful - based on the interception data at the end of May 1916, an English naval armada was sent to meet the German forces, which ended in the famous Battle of Jutland.

German radio intelligence was not so successful, but it did a good job of intercepting Russian negotiations, the lion's share of which was broadcasted in plain text. The story about this will be in the second part of the cycle.

To be continued….