- Author Matthew Elmers elmers@military-review.com.

- Public 2023-12-16 21:49.

- Last modified 2025-01-24 09:17.

And a bad blacksmith happens to forge a good sword.

Japanese proverb

Kaji is a blacksmith-gunsmith, "sword-forging", and the people of this profession in feudal Japan were the only ones who stood on the social ladder along with the samurai. Although de jure they belonged to artisans, and those according to the Japanese table of ranks were considered lower than the peasants! In any case, it is known that some emperors, not to mention the courtiers and, in fact, samurai, did not hesitate to take a hammer in their hands, and even engage in the craft of a blacksmith. In any case, Emperor Gotoba (1183 - 1198) declared the making of swords to be an occupation worthy of princes, and several blades of his work are still kept in Japan.

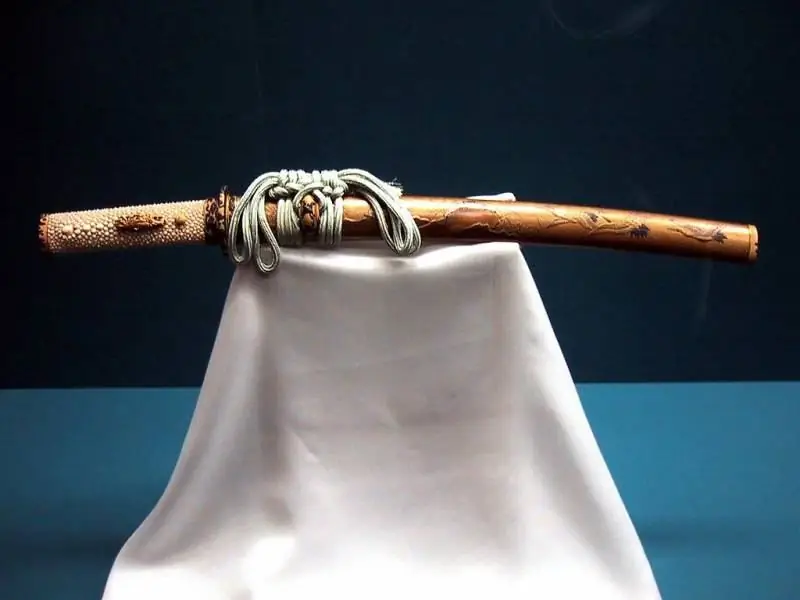

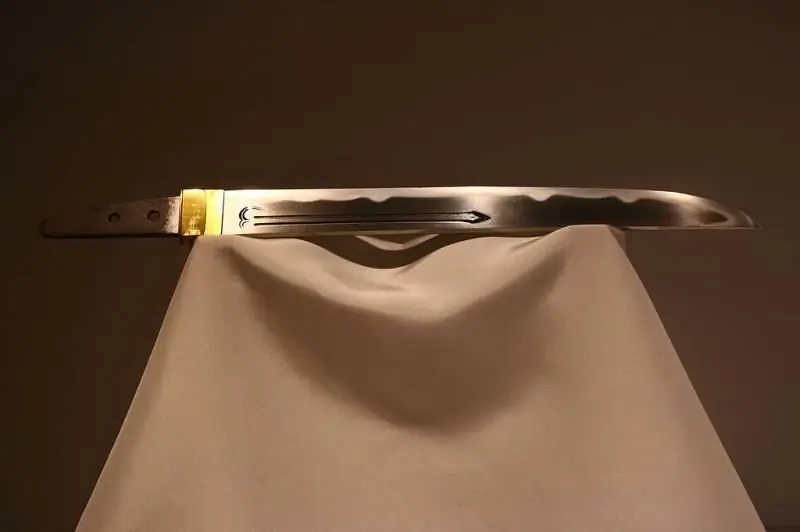

Wakizashi is the "short sword" of the Edo era. Tokyo National Museum.

The hardness and sharpness of Japanese swords is legendary, as is the art of blacksmithing itself. But in principle, in their manufacture there is no such big difference from the technical process of forging a European blade. However, from a cultural point of view, forging a Japanese sword is a spiritual, almost sacred act. Before him, the blacksmith goes through various prayer ceremonies, fasting and meditation. Often he also dresses in the white robes of a Shinto priest. In addition to this, the entire smithy must be thoroughly cleaned, which, by the way, women have never even looked into. This was done primarily in order to avoid contamination of steel, but women are from the "evil eye"! In general, the work on the Japanese blade is a kind of sacred rite, in which each operation during the forging of the blade was considered as a religious ceremony. So, to carry out the last, most important operations, the blacksmith wore a kariginu court ceremonial costume and an eboshi court hat. For all this time, the forge of kaji became a sacred place and a shimenawa straw rope was stretched through it, to which paper strips of gohei were attached - Shinto symbols designed to scare away evil spirits and summon good spirits. Every day before starting work, the blacksmith poured cold water over him for purification and begged the kami for help in the work ahead. No member of his family was allowed to enter the forge, except for his assistant. Kaji food was cooked on a sacred fire, on sexual relations, animal food (and not only meat - that goes without saying, Buddhists did not eat meat, but also fish!), The strictest taboo was imposed on strong drinks. The creation of a perfect blade (and a self-respecting blacksmith broke unsuccessful blades without any pity!) Often required work for quite a long time.

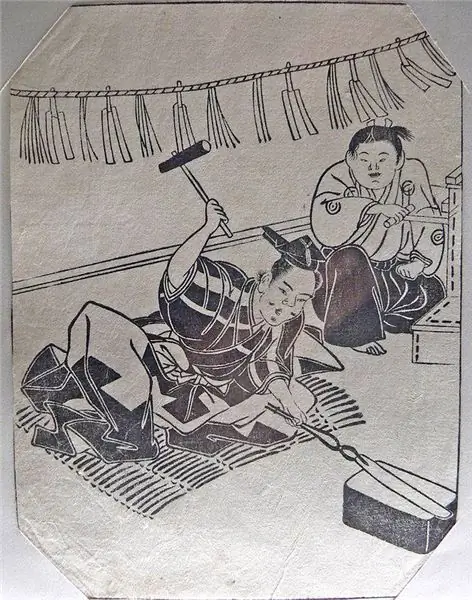

Scene from the 10th century the master Munetika forges the sword "ko-kitsune-maru" ("fox cub") with the help of the fox spirit. Engraving by Ogata Gekko (1873).

How long this time was can be judged by the information that has come down to us that in the VIII century it took a blacksmith 18 days to make a tati sword strip. Another nine days was required for the silversmith to make the frame, six days for the varnisher to lacquer the scabbard, two days for the leather master, and another 18 days for the workers who covered the sword hilt with stingray leather, braided it with cords, and assembled the sword in one unit. The increase in the time required to forge a strip of a long sword was noted at the end of the 17th century, when the shogun called on blacksmiths to forge swords directly in his palace. In this case, it took more than 20 days to make just one roughly polished sword strip. But the production time was sharply reduced if the blade itself was shortened. Thus, it was believed that a good blacksmith could make a dagger strip in just a day and a half.

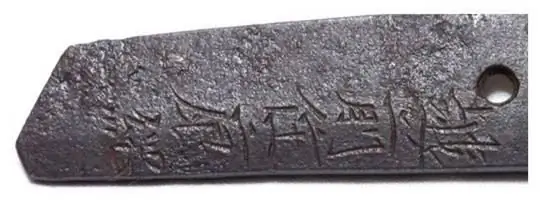

The shank of the blade with the signature of the blacksmith.

The forging process was preceded by the steel refining process, which in the old days was carried out by the blacksmiths themselves. As for the sources of raw materials, they - magnetite iron ore and iron-containing sand - were mined in different provinces. After that, this raw material was processed into raw steel in special furnaces of the Tatars. This oven was, in fact, an improved model of a cheese-blowing oven, which was widely used both in the West and in the East, but its principle of operation is the same. From the 16th century, iron and steel imported from abroad began to be used more often, which greatly facilitated the work of blacksmiths. Currently, there is only one Tatara furnace in Japan, in which steel is brewed exclusively for the manufacture of swords.

A depiction of the stages of forging during the Edo period.

The most important aspect when forging a Japanese sword is that the blade has a hardening that is different from the rest of the blade body, and the blades themselves are usually forged from two parts: the core and the sheath. For the shell, the blacksmith chose an iron plate of mild steel and lined it with pieces of hard steel. Then this package was heated over a pine coal fire and welded by forging. The resulting block was folded along and (or) across the axis of the blade and welded again, which subsequently gave the characteristic pattern. This technique was repeated about six times. During the work, the bag and tools were repeatedly cleaned, so that extremely clean steel was obtained. The whole trick here was that when metal layers of different strengths were superimposed on each other, large carbon crystals break, which is why the amount of contamination in the metal decreased with each forging.

Blade after forging and hardening before polishing.

It should be noted here that, unlike European Damascus steel, the point here is not in welding steels of different quality to each other, but in homogenizing all their layers. However, some of the unbonded layers in the metal still remained, but it provided additional toughness and amazing patterns on the steel. That is, Japanese folding, like Damascus forging, is a metal refining process, the purpose of which is to improve the quality of the starting material. For the shell of a Japanese sword, three or four such pieces are made, which, in turn, are forged again and repeatedly wrapped in one another. Different folding methods give a variety of types of patterns on the finished blade. So a piece of steel arose, consisting of thousands of layers firmly welded to each other, and its core was of pure iron or mild steel, which was also pre-folded and forged several times.

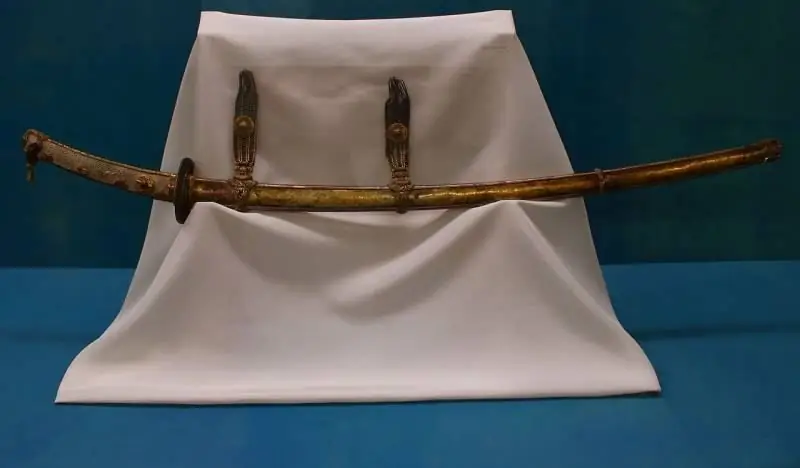

A tachi sword by Master Nagamatsu. Tokyo National Museum.

The next step was to weld the casing to the core. The standard process consisted of inserting the core into a V-shaped sheath and hammering to the desired shape and thickness. The blade, which was essentially finished, now faced the most difficult operation - hardening. Here we note a significant difference from the European sword. He was dipped in a red-hot state in water or oil as a whole. But the blank of the Japanese sword was covered with a mixture of clay, sand and charcoal - the exact recipes of this mixture were kept in strict confidence, and of different thickness. A very thin layer of clay was applied to the future blade, and on the side and back sides - on the contrary, almost half a centimeter thick. A small section of the back side was also left free on the tip in order to harden this part of it. After that, the blade was laid with the blade down on the fire. In order for the blacksmith to be able to accurately determine the temperature by the color of the glow, the forge was darkened or generally worked at dusk, or even at night. This color is indicated in some historical sources as "February or August moon".

Quenching process: on the right, a blade covered with clay before quenching. Left - the structure of the same blade after hardening.

When this glow reached the required value, the blade was immediately immersed in a bath of water. The part of the blade, covered with a protective layer, naturally cooled down more slowly and, accordingly, remained softer than the blade. Depending on the method, tempering was followed immediately after hardening. To do this, the blade was again heated to 160 degrees Celsius, and then again sharply cooled. The vacation could be repeated several times as needed.

The tachi sword was a horseman's sword, therefore it had attachments for wearing on the belt.

In the process of hardening, the crystal structure of steel changes greatly: in the body of the blade, it contracts slightly, and on the blade it stretches. In this regard, the curvature of the blade can change by up to 13 millimeters. Knowing about this effect, the blacksmith must, before hardening, set the blade to a lower curvature than that which he wants to get from the finished product, that is, to make it less curved at first. Despite this, in most cases, the blade might still need some work. It was carried out by placing the blade with its back on a red-hot copper block, after which it was cooled again in cold water.

Swordsmen and shooters at work. Old Japanese engraving.

The finished blade was carefully ground and polished (which often took up to 50 days!), While other artisans made mounts for it. Here there is often confusion in terms - "grinding" and "polishing" in Japan are identical concepts, and this is an inseparable process.

Moreover, if European blades usually consist of two chamfers, and their blade forms another narrow outer chamfer, then the Japanese blade has only one chamfer on each side, that is, there are only two of them, not six. Thus, when "sharpening" it is necessary to process the entire surface of the blade, which is why both sharpening and polishing are a single process. This technology produces a really very sharp razor-like blade and gives it a geometry that is great for cutting. But it also has one big drawback: with each sharpening, the surface layer is removed from the entire blade, and it "grows thin", and becomes thinner and thinner. As for the sharpness of such a blade, there is a legend that when the master Muramasa, proud of the unsurpassed sharpness of the sword he had made, thrust it into a fast stream, the leaves floating with the flow hit the blade and cut in two. Another, equally famous in terms of sharpness, the sword was called "Bob" only because the fresh beans falling on the blade of this sword, made by the master of Nagamitsu, were also cut in half. During the Second World War, one of the masters cut off the barrel of a machine gun with a sword, about which a film was supposedly even made, but later it seemed that it was possible to prove that this was nothing more than a propaganda trick designed to raise the morale of Japanese soldiers!

The hilt of a Japanese sword. The cords are clearly visible, the skin of the stingray, which covered its handle, the meguki fastening pin and the manuki decoration.

When polishing, Japanese craftsmen usually used up to twelve, and sometimes up to fifteen grinding stones with different grain sizes, until the blade received this very famous sharpness. With each polishing, the entire blade is processed, while the accuracy class and quality of the blade increases with each processing. When polishing, various methods and grades of polishing stone are used, but usually the blade is polished so that such forging and technical subtleties are distinguished on it,like jamon - a hardening strip from the surface of a blade made of especially light crystalline steel with a boundary line, which is determined by the clay cover applied by a blacksmith; and hada - a grainy pattern on steel.

Continuing to compare European and Japanese blades, we will also note that they differ not only in their sharpening, but also in the cross-section of the katana blades, knightly long sword and various sabers. Hence, they have completely different cutting qualities. Another difference lies in the distal narrowing: if the blade of a long sword becomes significantly thinner from the base to the point, the Japanese blade, which is already significantly thicker, practically does not become thinner. Some katanas at the base of the blade have a thickness of almost nine (!) Millimeters, while by yokote they become thinner only up to six millimeters. On the contrary, many Western European long swords are seven millimeters thick at the base, and become thinner towards the tip and are only about two millimeters thick there.

Tanto. Master Sadamune. Tokyo National Museum.

Two-handed sabers were also known in Europe, and now they came closest to Japanese swords. At the same time, no matter how much you compare Japanese nihonto and European sabers and swords, it is impossible to get an unequivocal answer, which is better, because they did not meet in battles, it hardly makes sense to carry out experiments on today's replicas, and to break valuable old ones for this swords hardly anyone dares. So there remains a vast field for speculation, and in this case, it is unlikely that it will be possible to fill it with reliable information. This is the same as with the opinion of a number of historians about the relatively low or, on the contrary, very high efficiency of the Japanese sword. Yes, we know that he chopped down dead bodies well. However, at the same time, the Japanese historian Mitsuo Kure writes that a samurai armed with a sword and wearing an o-yoroi armor could neither cut the enemy's armor with them, nor finish him off!

In any case, for the Japanese samurai, it was the sword that was the measure of everything, and the blades of famous masters were the most real treasure. The attitude towards those who forged them was also corresponding, so that the social position of a blacksmith in Japan was determined mainly by what swords he forged. There were many schools that were sensitive to the technologies they developed and carefully kept their secrets. The names of famous gunsmiths, such as Masamune or his student Muramasa, were on everyone's lips, and almost every samurai dreamed of possessing swords of their development. Naturally, like everything mysterious, the Japanese sword gave rise to many legends, so today it is sometimes simply impossible to separate fiction from truth and determine where is fiction and where is a real historical fact. Well, for example, it is known that the blades of Muramasa were distinguished by the greatest sharpness and strength of the blade, but also the ability to mystically attract misfortune to their owners.

Master Masamune's tanto blade - "it can't be more perfect." Tokyo National Museum.

But Muramasa is not one master, but a whole dynasty of blacksmiths. And it is not known exactly how many masters with that name were - three or four, but it is a historical fact that their quality was such that the most prominent samurai considered it an honor to possess them. Despite this, Muramasa's swords were persecuted, and this was almost the only case in the history of edged weapons. The fact is that the blades of Muramasa - and this is also documented - brought misfortune to the members of the family of Ieyasu Tokugawa, the unifier of the fragmented feudal Japan. His grandfather died from such a blade, his father was seriously wounded, Tokugawa himself was cut in childhood with the Muramasa sword; and when his son was sentenced to seppuk, it was with this sword that his assistant cut off his head. In the end, Tokugawa decided to destroy all of the Muramasa blades that belonged to his family. The example of the Tokugawa was followed by many daimyo and samurai of the time.

Moreover, for a hundred years after the death of Ieyasu Tokugawa, the wearing of such swords was severely punished - up to the death penalty. But since the swords were perfect in their fighting qualities, many samurai tried to preserve them: they hid, reforged the master's signature so that one could pretend that it was a sword of another blacksmith. As a result, according to some estimates, about 40 Muramasa swords have survived to this day. Of these, only four are in museum collections, and all the rest are in private collectors.

Koshigatana of the Nambokuch-Muromachi era, XIV-XV centuries. Tokyo National Museum.

It is believed that the Nambokucho period was the era of the decline of the great era of the Japanese sword, and then, due to the increase in their mass production, their quality deteriorated greatly. Moreover, as in Europe, where blades of the "Ulfbert" brand were the subject of numerous speculations and forgeries, so in Japan it was customary to forge blades of famous masters. Moreover, just like in Europe, the famous sword could have its own name and was inherited from generation to generation. Such a sword was considered the best gift for a samurai. The history of Japan knows more than one case when the gift of a good sword (a famous master) turned an enemy into an ally. Well, in the end, the Japanese sword gave rise to so many different stories, both reliable and fictional, related to its history and use, that it is sometimes difficult to separate truth from fiction in them even for a specialist. On the other hand, they are undoubtedly very useful both for filmmakers making films "about samurai" and for writers - authors of romantic books! One of them is the story of how one old oil merchant scolded Ieyasu Tokugawa, for which one of his associates slashed him in the neck with a sword. The blade was of such quality and passed through her so swiftly that the merchant took a few more steps before his head rolled off his shoulders. So what was it in Japan, and every samurai had the right to "kill and leave", ie to kill any member of the lower class who, in his opinion, committed an offensive act for his honor, and all the lower classes, willy-nilly, had to admit it.

So the samurai used their sword to finish off a defeated enemy.

But the masters who made the armor did not enjoy the recognition of equal blacksmiths in Japan, although there were known whole families of famous master armormen who passed on their skills and secrets from generation to generation. Nevertheless, they quite rarely signed their works, despite the fact that they produced products of amazing beauty and perfection, which cost a lot of money.

P. S. Finally, I can inform all VO readers interested in this topic that my book “Samurai. The first complete encyclopedia”(Series“The Best Warriors in History”) was out of print. (Moscow: Yauza: Eksmo, 2016 -656 p. With illustrations. ISBN 978-5-699-86146-0). It included many materials from those that were published on the pages of VO, but some others supplement - something from what was here is not in it, something is given in more detail, but something from what is in book, it is unlikely to appear here for thematic reasons. This book is the fruit of 16 years of work on the topic, because my first materials on samurai and ashigaru were published exactly 16 years ago - these were two chapters in the book "Knights of the East". Then in 2007 a book for children was published in the publishing house "Rosmen" - "Atlas of the Samurai" and many articles in various refereed publications. Well, now this is the result. It's a bit of a pity, of course, to part with this topic forever, and to know that you will never write anything equal to this book. However, there are new topics, new works ahead. I am obliged to note (I simply must, as it should be!) That the book was prepared with the support of the Russian State Scientific Fund, grant No. 16-41-93535 2016. A significant amount of photo illustrations for her was provided by the company "Antikvariat Japan" (http / antikvariat-japan.ru). Cover art by A. Karashchuk. A number of color illustrations are provided by OOO Zvezda. Well, work on new books has already begun …