- Author Matthew Elmers elmers@military-review.com.

- Public 2023-12-16 21:49.

- Last modified 2025-01-24 09:17.

We live in a fort

We eat bread and drink water;

And how fierce enemies

They will come to us for pies

Let's give the guests a party:

Let's load the buckshot cannon.

A. S. Pushkin. Captain's daughter

Museums of the world. Windolanda is an ancient Roman military camp in the north-east of England, near Hadrian's Wall. It was built around 85 AD. NS. and lasted until 370 AD. The camp garrison guarded the Roman Steingate Road from the Tyne River to the Solway Firth, which connected the Roman settlement of Luguvalium (present-day Carlisle) and the military camp of Coria (present-day Corbridge). Quite a few similar military camps have been found along the wall; many of them have also been turned into museums. But Vindolanda is known primarily for the fact that unique wooden tablets were found here, which turned out to be the oldest written documents found at that time in Great Britain (only in 2013, more ancient Roman tablets were found in London). And today our story will go about this interesting place.

And it so happened that when the Romans, moving farther and farther north, reached the border with Scotland, they realized that there was no point in going further. There were only completely wild Picts, which there was no point in conquering. Therefore, it was decided to fence off from them with a wall. And such a wall, named after the emperor Hadrian's wall, was built. Somewhere of stone with towers and buttresses, somewhere in the form of an earthen rampart lined with turf, it crossed the northern part of Britain at its narrowest point, from Carlisle to Newcastle, and had a total length of 117.5 km. Along its entire length, 150 towers, 80 outposts and 17 large forts were erected, in which the Roman legions or part of the allies were quartered.

One of these forts (in fact, it was a camp, a typical camp of the Roman legion) just became Vindolanda, built, by the way, long before the wall itself, namely around 85 AD, while the wall began to be built only in 122 year.

A ditch and rampart, reinforced with turf, in the shape of a rectangle, where there were leather tents - one for 10 people. But later the camp was rebuilt and expanded, and the tents were first replaced with wooden barracks, then with stone barracks (from the second half of the 2nd century). They built camps and lived in them auxiliaries - auxiliary units of the Roman army, whom the Romans recruited from the inhabitants of the conquered peoples, promising them Roman citizenship for this.

The earliest Roman forts in Windoland were built of wood and sod, and their remains are today buried four meters deep in anoxic waterlogged soil. There are five wooden forts built (and destroyed) one after the other. The first, a small fort, was probably built by the 1st Tungrian Cohort around 85 AD. Around 95 A. D. it was replaced by a larger, already wooden fort built by the 9th Batavian Cohort, a mixed infantry and cavalry unit of approximately 1,000 men. This fort was renovated around AD 100 by soldiers of the Roman prefect Flavius Cerialis. When the 9th Batavian cohort in 105 A. D. NS. left the fort, it was destroyed. But then the 1st cohort of the Tungrians returned to Vindolandu, built a large wooden fortress there and remained in it until about 122 AD. Hadrian's Wall was not built, after which it was moved, most likely to Verkovitium (Fort Howteds). Since 213 A. D. here was located the IV cavalry cohort of Gauls. The total number of the camp garrison at this time also reached about 1000 people.

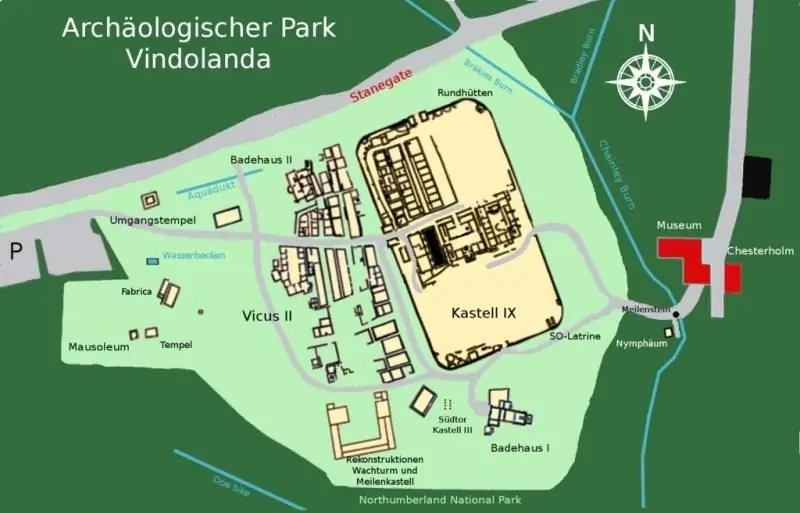

Top view of the settlement. The camp itself (and this is very clearly visible) is surrounded by a wall with rounded corners. There are towers on both sides of the gate. Below in the center are the terms.

When in 122-128. AD One and a half kilometers north of Vindolanda, the Hadrian Wall was erected, and a civil settlement appeared next to the camp walls - Vicus, most likely consisting of merchants and artisans who supplied the garrison with the products and various products it needed. Also, two whole bath complexes were built with the camp, which is not surprising if we remember the love of the Romans for cleanliness.

The later stone fort and the adjoining village remained in service until about 285, when they were abandoned for an unknown reason. True, the fort was rebuilt around 300, but people never returned to the settlement next to it. Around 370, the fortress was repaired for the last time, but after the Romans left Britain in 410, the camp was still inhabited. It was finally abandoned only around 900 - that's how long this place served people as a place of residence. It was even mentioned in Notitia Dignitatum (late 4th or early 5th century), as well as in the "Ravenna cosmography" (about 700). But then it was completely forgotten, so that the first post-Roman mention of the ruins existing here was made only in 1586 by the antiquary William Camden in his work "Britain".

When someone named Christopher Hunter visited the site in 1702, the baths still retained a roof. Then in 1715, an excise officer named John Warburton found an altar in the camp there, but decided to eliminate it. Finally, in 1814, the first true archaeological excavations were begun by the Reverend Anthony Headley at Windoland. Headley died in 1835, after which they stopped digging there again until 1914, when another altar was found, confirming that the Roman name of this place was precisely Vindoland, which was previously a matter of controversy.

In the 3rd century, the camp was in the shape of a rectangle measuring 155 × 100 meters, which was surrounded by a stone wall with rounded corners. There were four gates on each side of the world. In the center of the camp there was a house, square in plan, - the principium (headquarters building), and to the left and right of it stood the khorreum (grain warehouse) and the praetorium (the military leader's house). The rest of the territory was occupied by barracks. But in the camp there was still enough space for the temple of Jupiter Dolichen, and in the opposite corner - for a water tank.

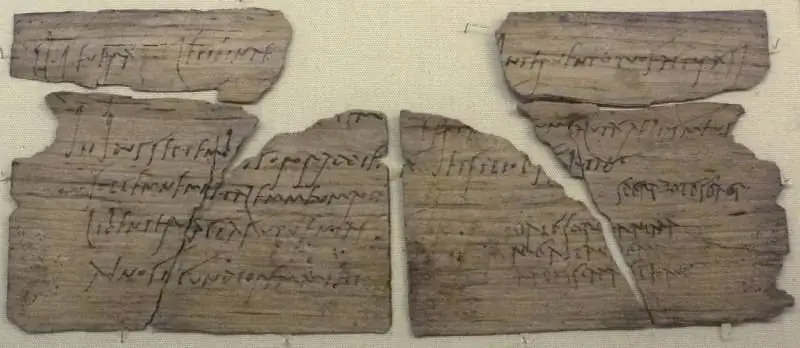

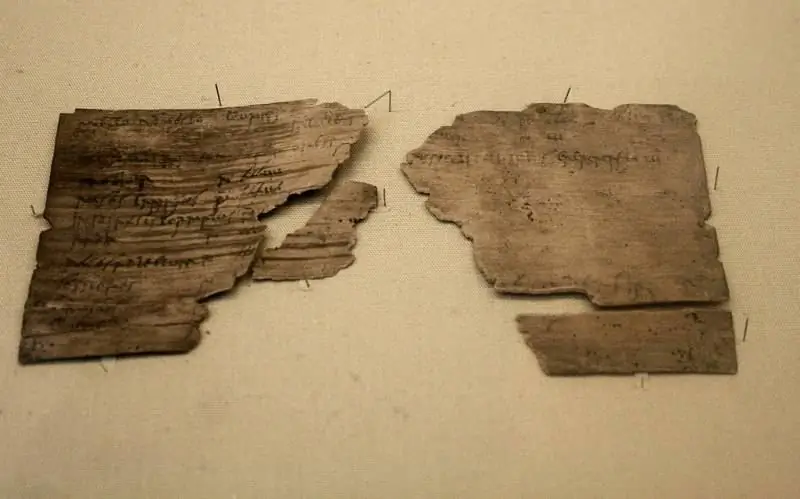

And there would be nothing particularly interesting in all this - well, you think, another fort of seventeen, if not for the unique properties of the local moist clay soil. We have a similar soil in Veliky Novgorod, and there it has preserved birch bark letters for us. But in Windoland, thanks to the same soil, such organic materials as wood, leather and fabric have been preserved, which would simply decay in other conditions. And here, too, they found ancient letters, only not on birch bark, but on wooden tablets!

The first such tablets were found here in 1973, and they were covered with charcoal ink. Most of the tablets date from the end of the 1st - the beginning of the 2nd century. AD, that is, the reign of the emperors Nerva and Trajan. The importance of this discovery can hardly be overestimated, because they describe the everyday life of an entire Roman camp, which cannot be read in any philosophical treatises. Moreover, there were a lot of these plates. By 2010, 752 tablets had been deciphered and published, and many more have been found. Today, these are, one might say, the most ancient writings in Great Britain, which are now kept not even in the local museum, but in the British Museum in London.

As for the Roman army contingent in the camp, its garrison consisted of both the infantry and the cavalry of the Auxiriarians, and not the Roman legionaries proper. Equitata Cohors IV Gallorum (Fourth Cohort of Gauls) was based here from the beginning of the third century. It was believed that this name by this time was already purely nominal, and whoever was not recruited into the auxiliary troops, but not so long ago during excavations they found an inscription proving that the Gauls were present here and that they even liked to be different from the Romans:

CIVES GALLI

DE GALLIAE

QUE BRITANNI

Which can be translated as follows: "Troops from Gaul dedicate this statue to the goddess Gaul with the full support of British troops."

An important role in the excavation of this place was played by the archaeologist Eric Bearley, who in the 30s of the twentieth century bought a house in Chesterholm, where the museum is now located, and began to excavate these places, after which this work was continued by his sons and grandson Dr. Andrew Bearley.

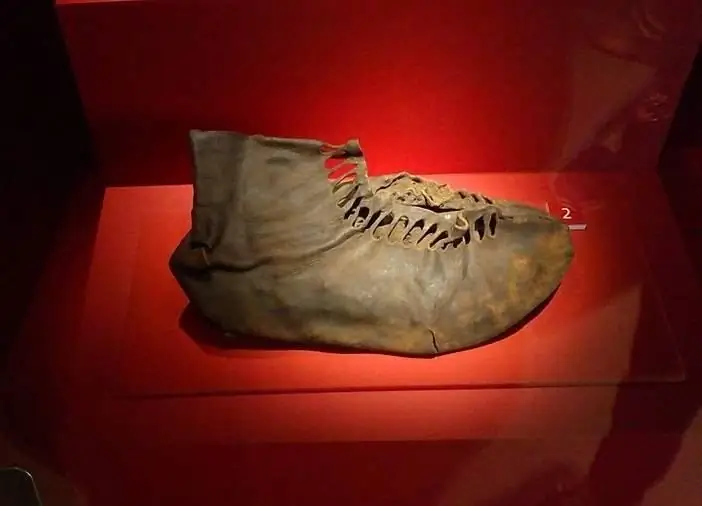

Excavations are carried out here every summer, with some of the excavations reaching a depth of six meters. Thousands of artifacts have been preserved in anoxic conditions at this depth, starting with the unique wooden tablets we have already named and more than 160 combs made of boxwood, which usually disintegrate in the ground, but here they have been preserved in an excellent way. All these "little things of life", however, give specialists the opportunity to get a complete picture of Roman life - both military and civil, here on the northern border of the empire. Studying spindles, for example. In the 3rd and 4th centuries A. D. NS. spinning was very developed in the vicinity of the fort. Well, the finds of shoes show that there were enough artisans who produced them.

They even found such a unique thing as Roman boxing gloves. They were discovered by a group led by Dr. Andrew Bearley in 2017. Found in Windoland, these gloves are similar to modern boxing gloves in almost every way, according to the Guardian newspaper, although they date back to 120 AD. That is, the Romans, it turns out, were fond of not only gladiator fights, but … also boxing!

Here, in the barracks, a large number of artifacts were found, including swords, tablets with records, textiles, arrowheads and other military supplies. The relative dating of the barracks indicates that they were built around 105 AD. During the 2014 excavation season, a unique wooden toilet seat was discovered.

In 2011, a museum appeared here - the Chesterholm Museum. A lot of finds made here are kept and demonstrated here, although the most valuable and interesting ones ended up in the treasury of the British Museum in London. But here you can see a wonderful reconstruction of an ancient Roman temple, as well as a Roman store, a residential building and even the camp itself, and all these reconstructions are equipped with audio presentations. There are Roman shoes, military equipment, some jewelry and coins found here, photographs of wooden tablets and several of these tablets themselves, transferred here from the British Museum. A Roman Army Museum was also opened at Camp Magnae Carvetiorum (modern Carvoran) and renovated and refurbished with a grant from the Heritage Foundation.

In 1970, the charity Vindolanda Trust was founded to manage the museum and the surrounding nature reserve. Since 1997, the trust has also run the Museum of the Roman Army in Carvoran, as well as one fort of Hadrian's Wall, which it bought back in 1972.

Thanks to the soil in Windoland, not only wooden tablets with inscriptions have survived, but also a lot of leather goods. So it comes as no surprise that her museum includes the largest collection of leather footwear in Roman Britain. They found leather patches, tent covers, horse harness, a lot of scrap and tannery waste. In total, more than 7,000 leather items were found, among which one of the latest finds is a completely unusual leather toy mouse.

Due to the coronavirus epidemic, the museum has recently closed. But his employees continued their work and, first of all, decided to disassemble everything that they simply could not reach before. They took an old bag full of scraps of leather, which seemed to contain nothing of value, and when all its contents were shaken up, they found … a mouse cut out of leather with paws, a tail and marks depicting fur and eyes. What it was, a child's toy or a funny souvenir, we will never know now. But the mouse, here it is, and they made it … God, how long ago it was made!

By the way, there really were a lot of mice in the camp. The fact is that under the floor of the granary they found just a lot of their skeletons. The floor was made of stone slabs, but grains, of course, fell into the cracks between them, and these mice ate them. And besides, if there was a horse cohort in the camp, then this clearly speaks of feeding the horses with oats, and where there is oats for the horses, there is a dining room for mice!

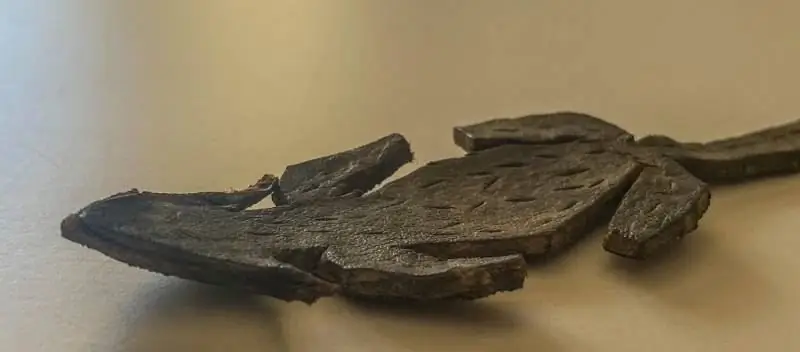

Another completely unique discovery was hipposandals - a metal "shoe" for horse hooves of a rather strange device. These are not horseshoes, the Romans knew horseshoes, just like spurs, but something that could be put on a horse's hoof and fixed on it. They are easy to carry around and just as easy to replace. But why they were needed, alas, none of the scientists really knows.

If they were put on horses' legs so that they jump in them, then there is a danger of injuring their legs when the horse goes at a trot or gallop and can touch one foot on the other. Therefore, there is a point of view that these shoes were intended for animals such as oxen, mules and donkeys, that is, slower ones.

It could be a device for hobbing horses in pasture: it is enough to put them on, tie them with a belt, and the horse will no longer be able to walk widely in them. Perhaps these were some kind of temporary "winter" horseshoes to put on bareback horses so that they would not slip on the ice. But then what prevented them from simply shoeing? Why did you need to communicate with these "devices"? There is also such a point of view that with their help, medical compresses were attached to the hooves. But whether this is so or not, we will most likely never know.

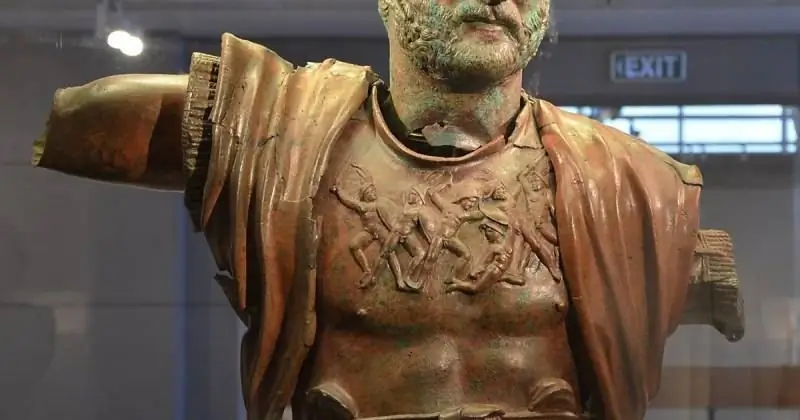

And in 2018, a beautifully made bronze palm was found there, resembling the size of a nursery. Dr. Andrew Bearley, CEO and director of the Windoland excavation site, believed this beautifully preserved artifact is of cult significance and may belong to the statue of Jupiter Dolichen, whose temple was excavated nearby in 2009.

In general, interesting finds follow one after another, it would be interesting to visit there, and the museum there will not leave indifferent any lovers of the history of Ancient Rome!