- Author Matthew Elmers elmers@military-review.com.

- Public 2023-12-16 21:49.

- Last modified 2025-01-24 09:17.

The chemical method of decorating armor, one might say, “untied the hands of the masters. After all, before they had to cut patterns on metal with the help of graters, while now practically the same effect was achieved by drawing on the metal with a sharp bone stick, and some waiting time until the acid did the work of the graders. The decorativeness of even relatively cheap armor immediately increased sharply, and their appearance approached the expensive armor of the nobility.

Well, let's start with this ceremonial armor made by the master Jerome Ringler, Augsburg, 1622. A pair of pistols signed by the master IR also relied on them. As you can see, this is nothing more than a set - armor for the rider and armor for the horse. They are decorated in the following way - this is a chemical coloring of the metal in brown, followed by gilding and painting on a gold plating. Both the rider's armor and the horse's armor are covered with the so-called images of "trophies", made up of various types of weapons and armor, while the medallion itself depicts the coat of arms.

This is how this armor looks when worn on a rider and on a horse!

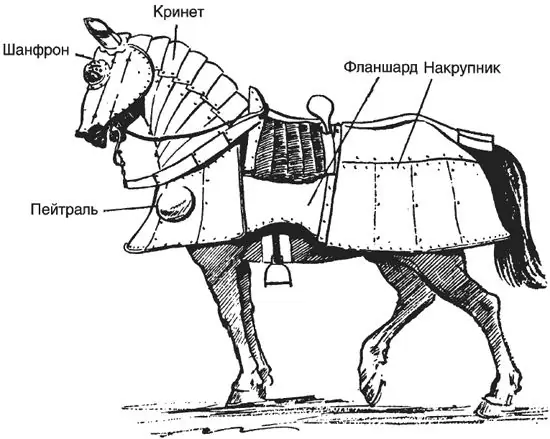

Names of parts of plate horse armor.

The perayl and chanfron are very visible.

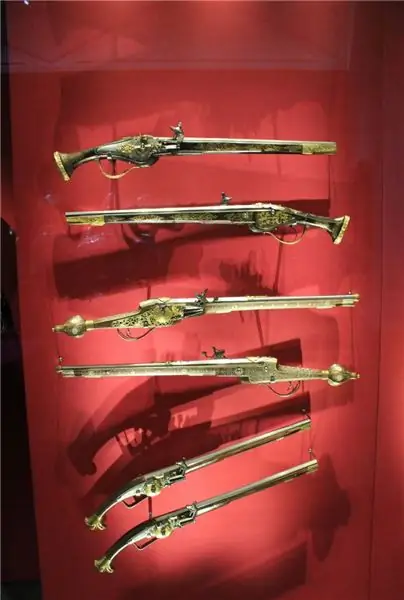

Well, these are pistols for this armor. The headset would be incomplete without them!

At the beginning of the 16th century, very original methods began to be used to decorate German armor. For example, surface engraving on blued metal. At the same time, the blued surface was covered with wax and on it, as in engraving on copper, a pattern or drawing was scratched with a sharp wooden stick. After that, the product was dipped in strong vinegar, and all the bluing left the cleaned places. All that remained was to remove the wax primer, and the armor had a clearly visible light pattern on a blue background. You could just scrape it out without resorting to a vinegar bath. They also worked on gold, that is, gilding deposited on blued metal, which made it possible to obtain "golden patterns" on steel. This technique was used by the masters of the 17th century.

Three pairs of pistols with wheel locks. Top and center: masters WH, NZ, NK, Suhl., 1610-1615 Below, Germany - 1635 Master unknown. Actually, all the other masters are also unknown. We know about the armor, who was hiding behind what "nickname", but the pistols - no!

Three more pairs. As you can see, something, but there were enough wheel pistols for the German cavalry during the Thirty Years War … Including the most luxurious ones!

The technology for working with mercury gold has been known for a long time. Therefore, another method of gilding was used, which in fact represented the "covering" of the armor (cladding) with gold foil. This technology consisted in the fact that the parts of the armor were heated to a high temperature, and then gold foil was applied to their surface and ironed with a special steel polisher, which made the foil very firmly connected to the metal. Armor from Augsburg and also in other places was decorated in this way. It is clear that skill was required here, as in any other business, but the technology itself was, as you can see, very simple.

Tournament armor of Elector Christian I of Saxony. The work of the master Anton Peffenhauser, Augsburg, 1582.

It is clear that such a noble lord as Christian I of Saxon simply should not have only one armored set. Well, what would his high-ranking acquaintances and friends think of him? Therefore, he had several armored headsets! This is, for example, ceremonial armor, both for a person and for a horse (that is, a complete knight's set, which often weighed 50-60 kg, which was taken for the weight only of the actual armor of the knight himself!), Which he made for him all the same renowned master Anton Peffenhauser from Augsburg, until 1591

Ceremonial armor with chanfron and armored saddle from Augsburg 1594-1599

Blackening or niello was one of the ancient methods of finishing weapons, and this method was known to the ancient Egyptians. Benvenuto Cellini described it in detail in his treatises, so that the masters of the Middle Ages had only to use it. The essence of this method was to fill the patterns on the metal with black, consisting of a mixture of metals such as silver, copper and lead in a ratio of 1: 2: 3. This alloy has a dark gray color and looks very noble against a light background of shiny metal. This technique was widely used by the gunsmiths of the East, and from the East it also came to Europe. It was used to decorate the hilts and scabbards of swords, but in the decoration of armor, as Vendalen Beheim writes about it, it was used relatively rarely. But again, only in Europe, while in the East, helmets, and bracers, and plates of yushmans and bakhters were decorated with black. In the Middle Ages, among Europeans, this technique was used mainly by Italians, and gradually it never came to naught, remaining a characteristic feature of the eastern, for example, Caucasian weapons.

Ceremonial armor commissioned by King Eric XIV of Sweden, circa 1563-1565 The figure holds a marshal's baton in his hand.

The inlay technology is no less ancient. The essence of inlaying is that a metal wire made of gold or silver is hammered into recesses on the surface of the metal. In Italy, this technology began to be used in the 16th century, although it was known in the West for a long time, since ancient times and was widely used to decorate rings, buckles and brooches. Then it was forgotten and spread again through the Spaniards and Italians who dealt with the Arabs. Since the beginning of the 16th century, the technique of inlaid metal has been very successfully used by Toledo armourers, masters of Florence and Milan, whose inlaid weapons were distributed throughout Europe and aroused admiration everywhere. The technology itself is very simple: grooves are made on the metal with a cutter or chisel, into which pieces of gold or silver wire are hammered. Then the inlaid parts are heated, and the wire is firmly connected to the base. There are two types of incrustation: the first is flat, in which the wire driven into the base is at the same level with its surface, and the second is embossed when it protrudes above the base surface and creates a certain relief. Flat inlay is easier, cheaper and more profitable, since it is enough to grind and polish it, as it is ready. But this method has its limitations. Inlaying is always done in thin lines and in areas of a relatively small area. Therefore, large areas have to be gilded with gold foil.

The same armor on the other side.

The second half of the 15th century was marked by the use of such a decorative technique, which was new for the arms business, as iron chasing. Gold chasing was known to different peoples, in different eras, and even back in the Bronze Age, and in Byzantium at its heyday it was almost the main branch of applied art. But this technology was still typical for working with soft metals, but iron does not belong to them in any way. And on what, on what iron was it to be minted? Therefore, only with the advent of plate armor, and even then not immediately, did the art of armourers reach such heights that they mastered the techniques of iron chasing, and were able to create beautiful knightly armor for the knights themselves, and also for their horses.

The horse forehead is amazing, and so is the petrail.

At first glance, the work seems to be simple. A drawing is made on the metal with an engraving needle, after which a three-dimensional figure or "picture" is knocked out from the inside, on which it is made, with the help of hammers and embossings of various shapes. But when it comes to iron, it becomes much more difficult to work, since the workpiece must be processed in a heated form. And if work on iron always starts from the "wrong side", then fine processing is carried out both from the front and from the back. And every time the product needs to be heated. Cities such as Milan, Florence and, of course, Augsburg were famous for their chased works.

One of the scenes on the right. Interestingly, King Eric XIV never received his luxurious armor, in my opinion, perhaps the most beautiful among all ever made. They were intercepted by his enemy, the Danish king, after which in 1603 they were sold to Elector Christian II of Saxony and thus they ended up in Dresden.

The decor of the armor of King Eric is downright unusually luxurious: in addition to the small decoration, it consists of six images of the exploits of Hercules. The decoration of the armor was made by the master from Antwerp Eliseus Liebaerts according to the sketches of the famous master Etienne Delon from Orleans, whose "small ornaments" were highly valued among gunsmiths and were widely used to decorate the most luxurious armor.

Hercules taming the Cretan bull.

Another technology used in the design of armor is metal carving. Italy also surpassed all other countries in the use of this technology in the 16th century. However, already in the 17th century, French and German gunsmiths managed to catch up and even overtake their Italian colleagues in the beauty of their products. It should be noted that chasing is usually done on sheet metal, but metal carving is used more widely. It can be seen on the hilts of swords, swords and daggers, it adorns rifle locks and firearm barrels, stirrups, horse mouthpieces and many other details and parts of weapons and armor. Both chasing and metal carving were used most often in Italy - in Milan, Florence, Venice, and later in Germany - in Augsburg and Munich, very often together with inlay and gilding. That is, the more techniques the master used, the more impressive armor they created.

Bumpkin. Rear right view.

Over time, different countries have developed their most popular techniques for decorating weapons and armor. For example, in Italy it was fashionable to create chased compositions on large round shields. In Spain, chasing was used in the design of armor and shields. At the beginning of the 17th century, they used chasing together with gilding, but the ornaments were not at all rich, so there was a clear decline in applied weaponry.

Bumpkin. Left rear view.

The last type of decoration for weapons and armor was enamel. It appeared in the early Middle Ages and was widely used in jewelry. Cloisonne enamel was used to decorate sword hilts and shields, as well as brooches - hairpins for cloaks. To decorate the hilts of swords and swords, as well as the sheathing of the scabbard, enamel works were carried out in France (in Limoges) and Italy (and in Florence). In the 17th century, artistic enamel was used to decorate the butts of richly decorated rifles, and most often - powder flasks.

Bumpkin. Left view.

Petrail view on the left.

A number of changes in the decor of the armor were associated with changes in the armor itself. For example, at the beginning of the 16th century. in Italy, copper horse armor spread and copper chasing became popular. But soon they abandoned this armor, since they did not protect against bullets and instead they began to use leather belts with copper plates in the places of their crosshairs, braiding the horse's croup and protecting well from chopping blows. Accordingly, these plaques-medals also began to be decorated …

We in the Hermitage also have similar headsets for a horse and a rider. And they are also very interesting. For example, this one from Nuremberg. Between 1670-1690 Materials - steel, leather; technologies - forging, etching, engraving. But this rider has something with his leg … "not that"! The armor is not worn on a mannequin, but simply fastened and mounted on a horse …

In this regard, knights in armor and on horseback from the Artillery Museum in St. Petersburg are not inferior to those of Dresden! Photo by N. Mikhailov