- Author Matthew Elmers elmers@military-review.com.

- Public 2023-12-16 21:49.

- Last modified 2025-01-24 09:17.

Among the visitors to the VO site there are many people interested in ancient technologies, and this is understandable. And we try to satisfy their curiosity as much as possible: we contact the craftsmen who use ancient technologies and make excellent replicas of the same products of the Bronze Age. One such master, Dave Chapman, Bronze Age Foundry owner, gunsmith and sculptor, lives in Wales, where he has a large house with a workshop and a glass studio, and his work is exhibited in the best museums in the world. Matt Poitras of Austin, Texas has been making impressive armor, and Neil Burridge has been casting bespoke bronze swords for 12 years.

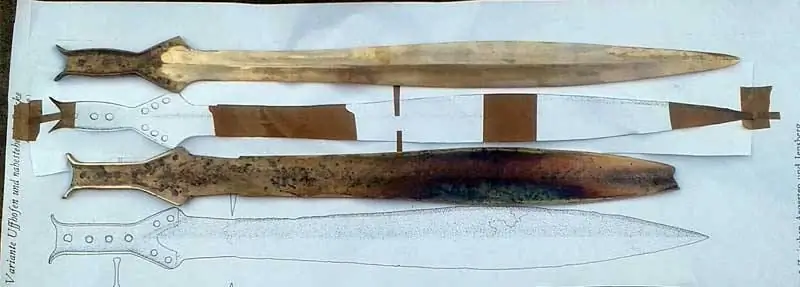

This is how the original samples get to Neil Burridge.

In this way they leave his workshop. Replica of the Wilburton Sword, made for the Museum in Lockerbie.

It is clear that such work is preceded by many different studies and analyzes. In particular, metallographic analysis is carried out, the composition of the metal is found out, in order to eventually get a completely authentic copy, not only in appearance, but also in material.

Samples of Neil Burridge products.

However, this is how archaeologists of all countries work. Especially recently, when they have access to both spectral analysis and work with high-resolution microscopes. It happens that, examining the surface of certain products and the characteristic damage, real discoveries are made on them. So, for example, it was possible to prove that at first the ancient people did not throw spears with flint tips, but struck with them, and only after thousands of years did they learn to throw them at the target!

Items for the Shrevesbury Museum. The work of Neil Burridge. They will lie next to the originals, and people will be able to compare them and evaluate how much time has changed the originals.

However, sometimes the finds themselves help scientists. For example, there are many known finds of stone drilled axes. They have long been counted for hundreds of tons, produced in different places and belonging to different cultures. But the question is: how were they drilled? The fact is that the holes in them, like the axes themselves, were subsequently polished and traces of processing were thus destroyed. However, axes were found, unfinished with work, and now they very well show how and with the help of which they were drilled. Wooden sticks and quartz sand were used. Moreover, the "drill" rotated under pressure and rotated with great speed! That is, clearly not with your hands. But then what? Obviously, this was the oldest drilling machine, representing a combination of upper and lower supports and racks connecting them. In the upper support there was a hole into which a "drill" was inserted, on which a heavy stone was pressed, or the stone itself was put on it. The "drill" was then overwhelmed by the bowstring and quickly moved back and forth, while the bowstring rotated the drill at a very high speed. Interestingly, the images on the walls of Egyptian tombs confirm that the Egyptians used such bow-like machines to make vessels from stone.

But was this the only "machine" known to people of the Bronze Age?

It is known that in the Bronze Age, many burials were carried out in bulk mounds. Many such mounds were known on the territory of the USSR, where they began to be excavated back in the 30s of the last century. So in the last five years before the war, the famous Soviet archaeologist B. A. Kuftin began to excavate burial mounds in southern Georgia in the town of Trialeti, which in their appearance were very different from those known until that time in the Transcaucasus. That is, they were there, of course, but nobody dug them out. So Kuftin dug out the mound No. XVII, which was not the largest and not the most noticeable, but the burial items found in it turned out to be absolutely outstanding.

An unfinished stone ax of the early Bronze Age (c. 2500 - 1450 BC) from a museum in Pembrokeshire.

The burial was a large burial pit with an area of 120 m2 (14 m X 8, 5 m), 6 m deep, in which next to the remains of the deceased, among the many vessels standing along the edges, there was a silver bucket with amazing chased images.

Here it is, this silver "bucket". (Georgian National Museum)

But, of course, a truly luxurious goblet made of pure gold, decorated with filigree and grain, as well as precious stones, turquoise and light pink carnelian, which was found together with this bucket, was a completely exceptional find. The cup had no analogues among the discovered monuments of toreutics of the Ancient East, and for the Bronze Age on the territory of Georgia it was an amazing find.

Trialeti necklace: 2000 - 1500 BC.; gold, agate and carnelian. (Georgian National Museum)

Interestingly, despite its volume, the cup was very light. It was made, according to Kuftin, from one single piece of sheet gold, forged at first in the form of a narrow-necked oval-shaped bottle, the bottom half of which was then pressed inward, like the walls of a ball, so that the result was a deep bowl with double walls and on a leg, which formed the former neck of this bottle. Then an openwork slotted bottom was soldered to the bottom, and nests for stones made of filigree and decorated with grain were soldered to the entire outer surface of the goblet. The entire decoration of the cup walls looked like spiral volutes, also made of gold. The volutes were soldered to the surface of the vessel tightly, after which precious stones were inserted into the nests. B. A. Kuftin was delighted with the cup, and this is not surprising. After the war, the famous Soviet metallurgist F. N. Tavadze became interested in how this cup was made. He carefully studied it and came to the conclusion that, having described the technological methods of making the cup, Kuftin was wrong. He stated that thin sheet gold would not be able to withstand being re-pressed by a figured punch. And then it seemed strange to him that there were no traces of hammer blows on the surprisingly even walls of the cup, which would have produced such an indentation.

Here it is, this cup in all its glory! (Georgian National Museum)

Having considered all possible techniques, Tavadze and his colleagues decided that the pressure in the process of making the cup was carried out on a simple lathe, something similar to the machines that were then used by street knife grinders. This method is well known also to modern metalworkers.

This cup is very beautiful, to be sure! (Georgian National Museum)

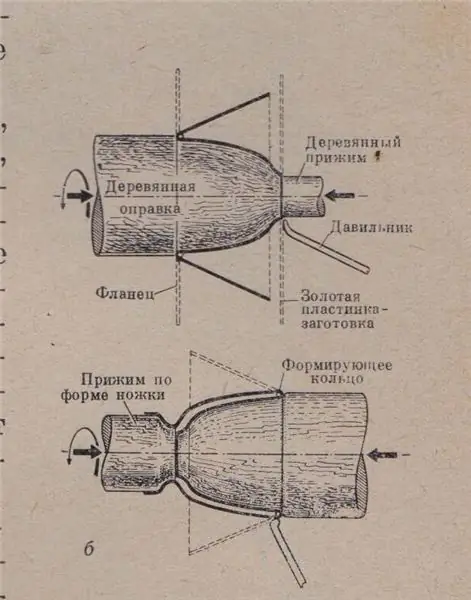

The process of making the cup in this case was carried out as follows: there was a wooden (and maybe metal) mandrel, turned to the shape of the product, which was installed in the spindle of this machine. A sheet of gold was applied to the surface of the mandrel, after which the machine was set in rotation, and a pressure press was manually pressed against the sheet, which was sequentially moved along the mandrel. Apparently, this primitive machine could not have enough revolutions, which is not surprising, because it also had a manual drive. Therefore, in order to avoid warping the squeezed out gold sheet, the mandrel from the end side had to be supported with a special support or a wooden clamp in order to extinguish the pressure of the pressure press with its help.

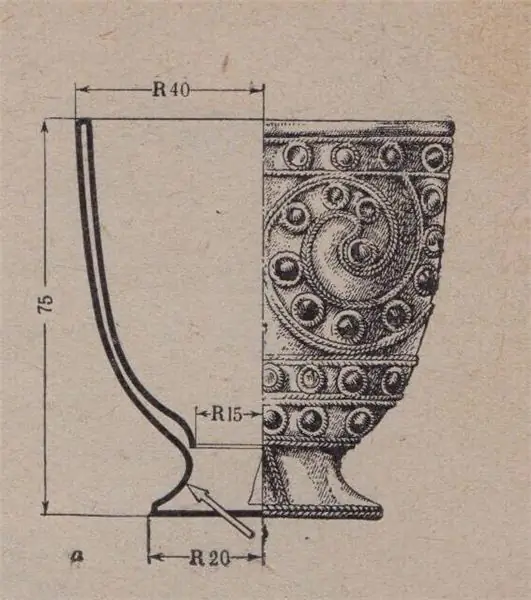

Cutaway Cup. The arrow indicates the bend of the leg, which could be obtained by changing the clamps.(based on the book by E. N. Chernykh “Metal - Man - Time! M.: Nauka, 1972)

That is, it was concluded that the manufacture of the gold cup could be carried out as follows: a round gold sheet-blank, cut from a previously forged sheet, was applied to a mandrel. First, the very bottom of the cup was obtained. Then, the inner walls were gradually squeezed out by a pressure tool along a mandrel, the shape and dimensions of which repeated the shape of the inner part of the goblet. Then the rest of the workpiece was gradually turned in the opposite direction by the pressure press, grasping the previously extruded part, and passed to the lower part of the cup. At the same time, the clamp was changed, and the new clamp had the shape of a leg. Well, after the end of extrusion, the excess part of the metal was cut off, and then the mandrel was removed, the clamp was removed and the second (lower) bottom of the cup was soldered.

The technology of making a cup from Trialeti (based on the book by E. N. Chernykh Metal - man - time! M.: Nauka, 1972)

So our distant ancestors were very resourceful and inventive people, and did not stop at difficulties, but solved them in the most rational way, and even saved precious metal at the same time! After all, this goblet could have been easily cast from gold by the “lost shape” method, but they preferred to make it from a thin gold leaf!

P. S. The author is grateful to Neil Burridge (https://www.bronze-age-swords.com/) for providing photographs of his work and information.