- Author Matthew Elmers elmers@military-review.com.

- Public 2023-12-16 21:49.

- Last modified 2025-01-24 09:17.

In the XVI century. Western European armor masters reached the pinnacle of their skill. It was during this time that the most famous and richly decorated plate armor was created.

Workshops were scattered across many commercial and economic centers of Western Europe: the largest of them are Milan, Augsburg, Nuremberg, Solingen, Toledo, etc. Usually they were located where the conditions for production were the most favorable. These conditions were: stocks of wood for coal, water resources for driving hammers and polishing wheels, and, of course, proximity to suppliers of iron and steel. Trade arteries were also very important - water and land routes for the transportation of raw materials and finished products. And, of course, it was impossible to do without customers, and customers, preferably regular ones. A considerable income was brought by orders from the court and knighthood. However, government orders for the mass production of weapons and armor for the troops were of much greater importance for the economic development of the workshops.

The workshops that existed at that time supplied military equipment, weapons and armor for entire armies, especially during the many wars of the era. The differences in the manufacture of armor and weapons for the nobility and for the soldiers were fundamentally small (except for engraving and decoration), but nevertheless it was not easy to combine both processes (piece work and mass production) “under one roof”.

It should be noted that the armor of famous masters could cost very large money, sometimes whole fortunes. As an example, we can cite one entry from the expenditure book of the Spanish court for 1550: "Colman, the Augsburg armored man - 2000 ducats at the expense of 3000 for the made armor" [Etat de dpenses de la maison de don Philippe d'Autruche (1549-1551) // Gazettedes Beaux & Arts. 1869. Vol. 1. P. 86-87]. Ducat in Spain in the 16th century. - a gold coin weighing approximately 3.5 g, i.e. 3,000 ducats in terms of weight is just over 10 kg of fine gold. And, for example, good armor for the tournament of the Augsburg master of the 16th century. Anton Peffenhauser cost no less than 200-300 thalers, while ordinary mass armor for an ordinary soldier cost no more than 6-10 thalers. Thaler (or Reichstaler) in the Holy Roman Empire of the 16th century. - a silver coin weighing 29, 23 g (since 1566), i.e. 300 thalers in terms of weight is approximately 8, 8 kg of silver.

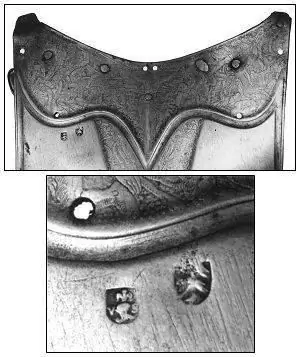

Becoming a master was not easy at all. In each of the cities listed above, there were a number of large non-specialized workshops owned by prominent families involved in the production of weapons. There was constant competition between them, while the manufacturers of weapons and armor were obliged to strictly comply with the requirements of the charter of the city guilds of gunsmiths. The guild carried out not only regular inspections of the quality of products before sale, but also carried out constant monitoring of how the apprentices and apprentices were trained. The shop guild appointed a special commission (some of the best craftsmen from different families) to control the quality of the products. She stamped the city mark on those parts of the armor that passed the test. Therefore, most of the armor and weapons of that time have 2 hallmarks - cities and craftsmen.

The stamp of the master Valentin Siebenburger (German Valentin Siebenburger, 1510-1564) in the form of a helmet with the letters "V" and "S" and the brand of the city of Nuremberg (right) on the breastplate of a cuirass made of armor made for the Brandenburg elector Joachim I Nestor or Joachim II Hector

Above: the brand of the master Kunz (Konrad) Lochner (German. Kunz (Konrad) Lochner, 1510-1567) in the form of a lion standing on its hind legs. Below: the stamp of the master Lochner (left) and the stamp of the city of Nuremberg

Sometimes craftsmen inserted their initials into the ornament when decorating armor (as a rule, in a conspicuous place).

The initials "S" and "R" by Stefan Rormoser (? -1565) from Innsbruck on the back of a helmet made of armor made for Duke of Styria Frans von Tuffenbach

The guild was an influential structure, and the masters obeyed the established rules. But not all and not always. There were masters who did not want to take them into account. So, the Nuremberg master Anton Peffenhauser, known for his graceful and highly artistic armor, did not have time to fulfill a large state order by the deadline. And then he began, through intermediaries, to buy ready-made armor from other masters and interrupt brands on them. This was not a crime, but it was contrary to the guild's charter. This became known. But the master had so much weight in society that the guild could not punish him with all its desire.

The apprentices were to be trained to make armor from start to finish. Training took, for example, in Augsburg or Nuremberg, four years, and then they worked the same amount, but as hired apprentices, and only then became qualified craftsmen. They were examined annually and at the same time issued a license for the manufacture of a certain part of the armor. The training was long and expensive, so most of the students finished their training, learning how to do only two or three details, which led to a narrow specialization. The number of apprentices and apprentices for a particular master was limited. For example, in Nuremberg, guild masters were allowed to have only two apprentices, and from 1507 their number was allowed to increase to four and one apprentice.

As a result of shop floor constraints, workshops, which were very small and specialized, had to cooperate with each other. However, it was often not a temporary partnership, but rather a permanent one. Arms marriages and dynastic inheritance of workshops were common. The experience of working together led to the cohesion of the workshops and the upholding of general interests of the shop. In addition, the specialization of labor also contributed to mass production, so the armor was made relatively quickly - the manufacture of good full armor without decorations took, on average, no more than 2, 5-3 months. It could take six months to make expensive ones with engraving.

Engraving, as a rule, was done by other craftsmen who specialized in this, who themselves developed the design or worked according to the approved master at the customer. But this type of decoration was quite rare and very expensive. A much more widespread technique in the 16th century. was acid etching. As a rule, this work was also not performed by the Master Armor.

Pompeo della Chiesa (Milan)

In the last quarter of the XVI century. Northern Italy became one of the producers of exquisite decorated armor, distinguished by highly artistic engraving in the style of rich Italian fabrics (Italian: i motivi a tessuto). Such armor, made using the technique of blackening and gilding, was covered with patterns that resembled the best textile samples. Palm branches, military fittings, trophies with elements of weapons were skillfully combined with engraved ornaments, images of allegorical figures and mythological characters of antiquity, coats of arms and mottos.

One of the largest European masters of defensive weapons was the outstanding Milanese gunsmith Pompeo della Chiesa or Chiese (Italian: Pompeo della Cesa). Among his customers were influential representatives of the nobility: the Spanish king Philip II of Habsburg, the Duke of Parma and Piacenza Alexandro Fernese, the Duke of Mantua Vincenzo I Gonzaga, the Grand Duke of Tuscan Francesco I Medici, Prince-Bishop of Salzburg Wolf Dietrich von Raithenauz and Geosarara of Herosorard and Geosarara a lot others. The armor made by him can never be confused with the work of other masters.

It is not known where and when he was born, there is no exact data on the years of his activity. The first documentary mention of the master Pompeo della Chiesa dates back to 1571 and is contained in a preserved letter from one of his customers - Duke Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy. According to some reports, since 1593, Pompeo, already an elderly man, did not work on orders himself, but still controlled the work of his workshop, in which his students worked [Fliegel St. Arms & Armor: The Cleveland Museum of Art. Harry N Abrams, 1999. P. 94.].

The gunsmith's workshop was located not in the city itself, but in the residence of the Milanese dukes - the Sforza castle (Italian: Castello Sforzesco), which undoubtedly indicated the high position of the master. The castle has survived to this day and is considered the prototype of some of the architectural forms of the Moscow Kremlin.

Main tower of the Sforza castle in Milan

The master signed his armor with the POMPEO, POMPE or POMP monogram. As a rule, this monogram was inscribed in a cartouche with some kind of image or coat of arms on one of the central parts of the armor (for example, a cuirass). On some later armor, instead of a monogram, there is the mark of Maestro dal Castello Sforzesco (in the form of a three-tower castle), i.e. masters from the Sforza castle, where, at least from the beginning of the XIV century. there was a weapons workshop.

Half-body armor of Pompeo della Chiesa. Around 1590

Stamp Maestro dal Castello Sforzesco

Dragon flying witch

Another half-armor of a master from the same period

Currently, there are about three dozen pieces of armor made by Pompeo della Chiesa that have survived in whole or in part. Weapon experts B. Thomas and O. Hamkber identified and described twenty-four pieces of armor made by Pompeo [Thomas B., Camber O. L'arte milanese dell'armatura // Storia di Milano. Milano, 1958. T. XI. P. 697-841]. Plus 6 more in various collections, including one partially preserved in Russia (the Military-Historical Museum of Artillery, Engineering Troops and Signal Corps in St. Petersburg).

Helmschmidt (Augsburg)

The largest centers for the production of defensive weapons in the Middle Ages and in the earlier modern times were the South German cities of Augsburg and Nuremberg. Among the Augsburg gunsmiths, a special place is occupied by the Kolmans family (German Colman), who received the nickname Helmschmidt (German Helmschmidt; literally "helmet smiths").

The hallmark of the master Helmschmidt (tournament helmet with a star). On the left - the stamp of the city of Augsburg (pine coniferous cone)

The family business was founded by Georg Kohlmann (d. 1495/1496). He was succeeded by his son, Lorenz Kohlmann (1450 / 1451-1516), he worked for Emperor Frederick III, and in 1491 he was appointed as the court armor of Emperor Maximilian I. It is believed that in 1480 he invented the "set" - a set of interchangeable elements, which in different combinations formed armor with different functions: for war or a tournament, for equestrian combat or foot combat. In 1490 Lorenz participated in the development of the famous elegant style, which later received the name of the experts "Maximilian" [Idem. Helmschmied Lorenz // Neue Deutsche Biographie. Bd. 8. S. 506].

Full Gothic armor of Emperor Maximilian I. Craftsman Lorenz Kohlmann from Augsburg. Around 1491 Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

His son Koloman Kolman (1470 / 1471-1532), along with the rest of the family, took the name Helmschmidt. Despite the fact that the grandson of Maximilian - Emperor Charles V - repeatedly invited Koloman to work in Spain, the numerous orders that were poured into him in his homeland prevented the gunsmith from leaving Augsburg. In 1525 Koloman appears to have prospered, having bought a house from the widow of the engraver Thomas Burgmire. The geography of his clientele extended to Italy. In 1511 he wrote a letter to the Marquis Francesca Mantuanska, in which he shared his thoughts on the creation of horse armor that would cover the head, body and legs of a horse.

Master Koloman Helmschmidt and his wife Agnes Bray. 1500-1505

Products bearing the Koloman Kohlmann brand or attributed to him on the basis of documentary evidence can be seen in museums in Vienna, Madrid, Dresden and in the Wallace Collection.

The largest number of surviving armors of these armourers was made by Desiderius Helmschmidt (1513-1578). In 1532 he inherited the workshops in Augsburg, which his father shared with the Burgmair family. At first, Desiderius worked with the gunsmith Lutzenberger, who married Desiderius' stepmother in 1545. In 1550 he became a member of the city council of Augsburg, and in 1556 he became the court gunsmith of Charles V. Subsequently, he served in the same position with Emperor Maximilian II. …

Full armor of Master Desiderius Helmschmitd from Augsburg. Weight 21 kg. Around 1552

One of the most famous pieces of armor of his work is in the Real Armería Museum in Madrid - a magnificent damask steel dress armor made for Philip II, signed and dated 1550 (the same armor for which Desiderius was paid 3000 ducats from the Spanish treasury) …

Damascus steel armor of Philip II. Master Desiderius Helmschmitd from Augsburg. 1550 Real Armería Museum, Madrid

Anton Peffenhauser (Augsburg)

Another Augsburg master Anton Peffenhauser (German Anton Peffenhauser, 1525-1603) was one of the best masters of the late Renaissance. It worked for over 50 years (from 1545 to 1603). Compared to his other contemporaries, most of the armor made by him has come down to us [Reitzenstein F. A. von. Anton Peffenhauser, Last of the Great Armorers // Arms and Armor Annual. Vol. 1. Digest Books, Inc., Northfield, Illinois. 1973. P. 72-77.].

Anton Peffenhauser worked in the city of Augsburg, an old German center for the production of armor, weapons, jewelry and luxury goods. From 1582 Anton Peffenhauser began to work for the Saxon court. For the electors Augustus, Christian I and Christian II, he made 32 armor, of which eighteen survived in the Dresden collection. In addition, the master's customers were the Portuguese king Sebastian I, the Spanish king Philip II, the Bavarian duke William V, the Duke of Saxe-Altenburg Frederick William I and others.

In style, Peffenhauser's armor ranges from richly decorated to very simple. His mark is one of the most famous embossed armor, according to legend, belonged to the Portuguese king Sebastian I (1554-1578) who died in the battle of El Ksar El Kebir in Morocco. The armor is currently kept at the Royal Armory in Madrid.

The mark of the master Peffenhauser is the so-called triskelion (Greek three-legged). This sign in the form of three running legs (Peffenhauser's legs are shackled with greaves and sabatons), emerging from one point, was an ancient symbol of infinity.

Full armor of the Duke of Saxe-Weimar Johann Wilhelm. Master Anton Pefenhauser. Augsburg. Weight 27.7 kg. 1565 g.

Half-armor of the Elector of Saxony Christian I. Craftsman Anton Pefenhauser. Augsburg. Weight 21 kg. 1591 g.

One of the twelve tournament half-armor, which were ordered as a gift to the Saxon Elector Christian I by his wife Sofia of Brandenburg from the Hohenzollern family. The armor is made of oxidized steel, decorated with metal etching and gilded. The etched pattern consists of large floral patterns curling from a central trunk, with etched lines and a gilded leaf pattern inside.

Now his armor is in the collections of the State Hermitage, in museums in Vienna, Dresden, Madrid, New York, the Armory, the Tower of London, the German National Museum in Nuremberg, in the arms collection of the Coburg Castle and in the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Source: S. V. Efimov. Cold beauty. Armor of the great European armourers of the 16th century in the collection of the Military-Historical Museum of Artillery, Engineering Troops and Signal Corps.