- Author Matthew Elmers elmers@military-review.com.

- Public 2023-12-16 21:49.

- Last modified 2025-01-24 09:17.

"… Removing a thick gold chain from his neck, the Marked One tore off it with his teeth a piece of four inches long and gave it to the servant."

("Quentin Dorward" by Walter Scott)

Let's start by defining what we're talking about here. Not about the chains mentioned in the epigraph. This is so … for beauty! It will talk about a very unusual piece of knightly equipment of a very specific era - about knightly chains for attaching weapons. But first, all the same, let us remember that people are naturally unreasonable and are often prone to at first glance irrational behavior, conditioned not by expediency, but … by fashion. Well, fashion is a kind of material or spiritual embodiment of that herd feeling that once made a person a person. To be like everyone else at a certain and very significant stage in its history meant the opportunity to eat, because those who were “not like everyone else” were either expelled, or even worse, they were simply eaten.

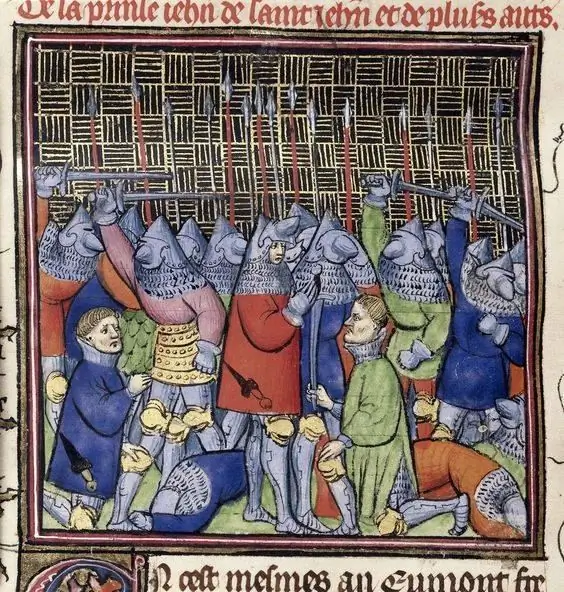

"Chronicles of St. Denis" - the last quarter of the XIV century. British Library. Surprisingly, but true - we see chains in large quantities on the effigies. But on medieval miniatures they … are not. On some, for example, like here, it is not even clear what the knights have daggers attached to.

This is how the concept of fashion arose, that is, a set of habits, values and tastes that are accepted by a certain environment and for a certain time. Then this aggregate or something taken separately from it changes so that what was fashionable yesterday becomes not fashionable today. It is obvious that fashion is the establishment of an ideology or style in various spheres of social life or the field of culture. And although fashion is far from always practical, people accept it in order not to "fall out" of their society.

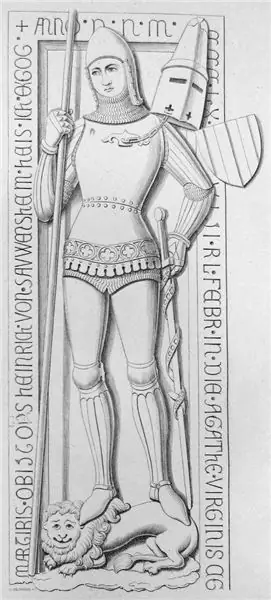

Since in our materials on VO we often gave photographs of effigies, it makes sense in this case to refer to their graphic drawings in order to see all the details as best as possible. This is one of the first effigies on which we see the chain going to the helmet. It depicts Roger de Trumpington. Trumpington Church in Cambridgeshire (c. 1289).

Roger de Trumpington. Reconstruction by a contemporary artist. Interestingly, the chain does not have a crutch and, most likely, is firmly attached to the edge of the helmet. Obviously, this was necessary in order not to lose the helmet. But what is surprising is, what then did the squire of this knight do, then what was he needed for? Was this very Trumpington, and all the other knights depicted here, who had helmets and chains, so poor that they could not afford to have a squire who carried their helmet for them and gave it to them as needed? It turns out that they had enough money for effigii, but not for a squire? Something is very doubtful!

Something similar at the end of the XIII century also took place among the knights of Western Europe, among whom it is suddenly incomprehensible why and completely incomprehensible why rather long chains came into fashion, which were attached to the hilts of their swords and daggers, while their other ends - and such the knight could well have had several chains, it happened even as many as four, were fixed on the chest. Although, how exactly this was done is still not known for sure. The reason is trivial: lack of data, since even effigies cannot show us everything. In some cases, however, there is enough information. For example, Roger's effigy to de Trumpington clearly shows that the only chain he has that leads to his helmet is attached to his … rope belt, which he is girded with.

On the effigy of John de Northwood (c.1330) from Minster Abbey on Sheppey Island (Kent), the chain to the helmet comes from the socket on the chest. It shows the hook on which this chain is put on. There are other, later effigies, on which such rosettes are made in pairs, for two chains, and are visible through the slots on the surcoat. And on what they are fixed there - on chain mail, or on armor made of plates, you cannot understand from the sculpture.

The effigy of Albrecht von Hohenlohe (1319). The hook attachment on the chest is very visible. And it clearly goes through the slot. It is not clear only where the scabbard of this dagger? And what were they attached to?

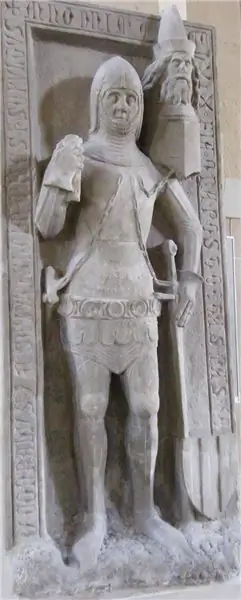

Heinrich von Seinsheim (1360). A very humble knight in regards to wearing chains, as he only has one. He has a large helmet on it, but a special piece is provided for attaching it to the woven jupon so that the heavy weight of the helmet would not tear it off. To keep the helmet on the chain, there were two cruciform holes in its lower part, and a barrel-shaped button at the end of the chain.

Johannes von Falkenstein (1365). But usually there were two chains. One went from the chest to the hilt of the dagger, and the other to the sword.

In the XIII-XIV centuries, chains leading to the handles of swords and daggers can be found on almost every knightly sculpture, especially in Germany, where the wearing of chains has gained particular popularity. It became fashionable here to wear four chains at once, although why so many of them are needed is not entirely clear. One to the sword, the other to the dagger, the third to the helmet. What was the fourth heading for?

Armor from Hirsenstein Castle near Passau. Consists of more than 30 plates and has attachments for four chains.

Reconstruction of "armor from Hirsenstein". Before us is the typical armor of the era of combined chain-plate armor - a brigandine made of plates, worn over a chain mail haberk, over which, in turn, a jupon made of fabric could be worn. Or he could not have dressed …

The effigy of Walter von Bopfinger (1336). Here on it we just see four chains, characteristic of the "armor from Hirsenstein." However, it is not entirely clear what this fourth chain is attached to. A T-shaped crutch is visible on one of them. But … nothing is attached to it! But effigia shows us a knight without cash clothing, which makes it possible to see his "armor" from horizontal metal strips, fastened by rows of rivets. That is, in 1336, there were already such cuirasses, just on many effigies and, accordingly, miniatures, we do not see them, since it was also fashionable then to wear jupon over armor!

Here is how, for example, on this "three-chain" effigy of Konrad von Seinheim (1369) from Schweinfurt. But here everything is clear, what is attached to, and it is also clear that under the fabric on his chest he has a metal cuirass!

Another "three-chain", and besides, also a painted paired effigy of Hennel von Steinach (1377). He has three chains and it seems that all three are fixed at one point.

The question arises, how were the chains attached to the handles? The effigy of Ludwig der Bauer (1347) shows this very well. This is the ring worn on the hilt. Apparently, it was sliding, since otherwise it would interfere with holding the weapon.

It is difficult to imagine that a person fights holding a sword in his hand, to the handle of which there is a four-foot chain (and often gold, that is, quite heavy!). After all, she probably interfered with him, because she could also wrap around the arm in which the knight held the weapon, and even catch hold of the horse's head and the weapon … of the enemy. Well, if the knight released the sword from his hand during the battle, then the chain could well get entangled in his stirrups. So then pulling the sword to the hand was most likely not at all as easy as it seems … However, the knights did not care about all these inconveniences in the XIV century. The famous British historian E. Oakeshott noted in this regard that they, perhaps, unlike us, had an idea of how to wield a sword and a dagger so that the chains did not get tangled and did not cling to anything. But how they did it, we do not know.

But this is a very interesting effigy of an unknown Neapolitan knight from 1300. As you can see, it has no chains yet. But the dagger, the so-called "eared dagger", has already appeared, and it hangs on a thin leather strap, but not on a knight's belt, like a sword, but on something that belts it with a surcoat. It would be more logical to hang it on the same belt, but for some reason this was not done. And before us is a knight clearly not poor. The metal leg armor has just appeared, and he already has it. And on the hands are protective plates made of "boiled leather" with embossing …

P. S.