- Author Matthew Elmers elmers@military-review.com.

- Public 2023-12-16 21:49.

- Last modified 2025-01-24 09:17.

I saw slaves on horses, and princes walking like slaves on foot.

Ecclesiastes 10.5: 7

Military affairs at the turn of the eras. In a transitional era, military affairs always develop rapidly. However, it is influenced by two opposite trends. The first is the power of traditions and the established opinion that the old is good for what is familiar. Second, you need to do something, because the old techniques don't work for some reason. So, Marshal of Henry VIII Thomas Audley demanded that none of the shooters should wear armor, except perhaps a Morion helmet, as he believed: "There can be no good shooter, be it an archer or arquebusier, if he serves dressed in armor."

As a result, when 40 soldiers were sent to France from Norich in 1543, 8 of them were archers who had a "good bow", 24 were "good arrows" (the number from the time of the Battle of Bannkoburn!), "Good sword", a dagger, but all the rest were "billmen", that is, spearmen armed with a "bill" ("ox tongue") - a spear 1.5 m long, with a knife-like blade, convenient in hand-to-hand combat. The sword and dagger supplemented the weapons, and they were all in armor, but in which ones, the document is not specified. By the way, this very "bill" was excluded from the armament of the British army by the decree of 1596. Now the infantry began to completely arm themselves only with pikes and arquebusses.

However, this is not entirely true. The Good English Bow was still in use. Moreover, there were military leaders who demanded and even sought the presence of infantrymen with two types of weapons in the British army - a lance and a bow. They were called that - warriors with dual weapons. Preserved illustrations depicting them and relating to 1620. They depict a typical pikeman in pikemen's armor and a morion helmet, who shoots from a bow and at the same time holds his pike in his hand. It is clear that this required a lot of dexterity and serious training. In addition, it seriously burdened the warrior. So the "double armament", although it looked theoretically very tempting, in practice did not take root. Moreover, such British historians as A. Norman and D. Pottinger report that after 1633, the pikemen's armor was not mentioned at all, that is, they did not wear anything except a helmet to protect them!

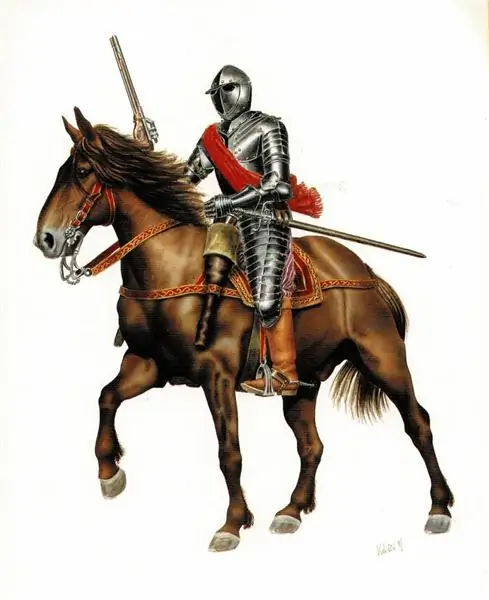

At the same time, the number of arquebusses was constantly growing and at the time of the death of Henry VIII, there were 7700 of them in the Tower's arsenal, but there were only 3060 bows. Knightly armor still existed, but in fact turned into a fancy metal costume. During the reign of Queen Elizabeth, the development of knightly armor continued, but they were worn mainly by her courtiers. In fact, battle armor at that time was only cuirassier armor, which was described in previous articles of this cycle, but they also underwent changes in accordance with the requirements of the time. True, back in 1632, the English historian Peter Young noted, the English cavalryman was still the same knight, although he did not have plate shoes, which were replaced by boots to his knees. He was armed either with a spear, but somewhat lighter in comparison with the knight's, or with a pair of pistols and a sword.

And then came the time of the civil war of 1642-1649, and the problem of the price of cuirassier armor became of decisive importance. The armies became more and more massive. In them, more and more commoners were called up, and it became an unaffordable luxury to buy them expensive plate gloves, plate legguards and fully closed helmets such as an armé with a visor. Armament all the time was simplified and cheapened. Therefore, it is not surprising that at this time such simplified types of protection as the "pot" ("pot") helmet for ordinary riders of the parliamentary army and "cavalier" helmets, which looked like a wide-brimmed hat with a sliding metal nose, popular in the king's army, appeared.

Very heavy sapper helmets with a strong metal visor appeared, which, as it is assumed, were worn not so much by the sappers themselves as by the military leaders who watched the course of the siege and fell under enemy shots. The "sweat" taken away on the helmets generally turned into a lattice of rods, that is, even the village blacksmiths could forge such "equipment".

The breast and back began to be covered with a cuirass to the waist, and the left hand was covered by a bracer, which protected the hand to the elbow, and was worn with a plate glove. But in the parliamentary army, such details of armor were considered "excess" and her "maiden cavalry had only helmets and cuirasses.

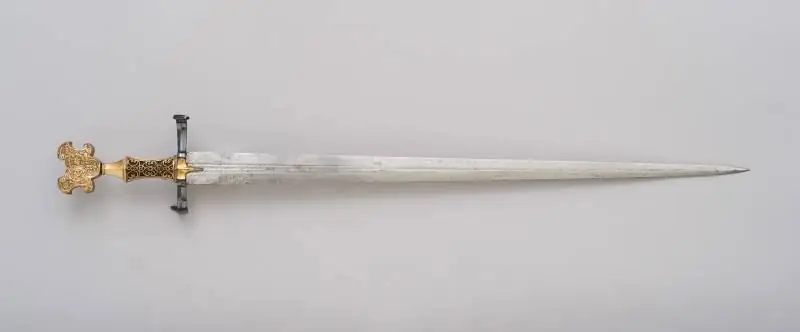

John Clements is a well-known specialist in the field of fencing reconstruction, in this regard, he points out that in the period from 1500 to 1600, the West European sword very quickly transformed into a rapier and a sword, and in the heavy cavalry the latter turned into chopping broadswords.

In fact, these were the same swords, but with a wider blade. In England, they began to be called the "basket sword", since the handle was protected by a real "basket" of iron rods or strips. Under the influence of the French school of fencing, a type of civil light epee with a blade 32 inches (81 cm) long also spread.

This is how, in fact, the equestrian men at arms gradually came to their decline and the year 1700 became its border. No, cuirassiers in shiny cuirassos from the armies of Europe did not go anywhere, but they no longer played such a significant role in wars as, say, the French pistoliers of the era of "war for the faith". It became clear that success in a battle depends on the skillful actions of the commander and the comprehensive use of infantry, cavalry and artillery, and not the complete superiority of any one type of troops, and, in particular, plate cavalry.

There is little left to tell. In particular, about the system of recognition "friend or foe" on the battlefield. After all, both there and there people fought in black armor, covering them from head to toe, or in yellow leather jackets, black cuirass and hats with feathers. How can we distinguish between friends and foes?

A way out was found in the use of a scarf, which was worn over the shoulder as a sash, and which the decor of the armor did not hide, who had it, of course, and indicated his nationality in the most noticeable way. In France, for example, in the 16th century, it could be black or white, depending on who its owner was fighting for - for Catholics or Protestant Huguenots. But it could also be green, or even light brown. In England, scarves were blue and red, in Savoy they were blue, in Spain they were red, In Austria they were black and yellow, and in Holland they were orange.

There was also a simplification of weapons. All kinds of picks and clubs from the arsenal have disappeared. The weapons of the heavy cavalry were a broadsword and two pistols, a light pistol and a saber, dragoons received a sword and a carbine, and horse pikemen - long pikes. This turned out to be quite enough to solve all the combat tasks of the era of developed industrial production, which Europe entered after 1700.

References

1. Barlett, C. English Longbowmen 1330-1515. L.: Osprey (Warrior series # 11), 1995.

2. Richardson, T. The Armor and Arms of Henry VIII. UK, Leeds. Royal Armories Museum. The Trusteers of Armories, 2002.

3. The Cavalry // Edited by J. Lawford // Indianopolis, New York: The Bobbs Merril Company, 1976.

4. Young, P. The English Civil War // Edited by J. Lawford // Indianopolis, New York: The Bobbs Merril Company, 1976.

5. Williams, A., De Reuk, A. The Royal Armory at Greenwich 1515-1649: a history of its technology. UK, Leeds. Royal Armories Pub., 1995.

6. Norman, A. V. B., Pottinger, D. Warrior to soldier 449-1660. A brief introduction to the history of British warfare. UK. L.: Weidenfild and Nicolson Limited, 1966.

7. Vuksic, V., Grbasic, Z. Cavalry. The history of fighting elite 650BC - AD1914. L.: A Cassel Book, 1993, 1994.

The end follows …