- Author Matthew Elmers [email protected].

- Public 2023-12-16 21:49.

- Last modified 2025-01-24 09:17.

The first part of the publication was devoted to the chronic deficiency of metals in Kiev and Moscow Rus. In the second part, we will talk about how in the 18th century our country, thanks to the factories of the Urals, became the world's largest producer of metals. It was this powerful metallurgical base that was the basis of all the successes of the Russian Empire from Peter I to the Napoleonic wars. But by the middle of the 19th century, Russia had lost the technological revolution in metallurgy, which predetermined its defeat in the Crimean War and the loss of Alaska. Until 1917, the country was unable to overcome this lag.

Iron of the Urals

For a long time, the development of the Urals was hampered by its remoteness from the main cities and the small number of the Russian population. The first high-quality ore in the Urals was found back in 1628, when the "walking man" Timofey Durnitsyn and the blacksmith of the Nevyansk prison Bogdan Kolmogor discovered metal "veins" on the banks of the Nitsa River (the territory of the modern Sverdlovsk region).

Samples of ore were sent "for testing" to Moscow, where the quality of the Ural iron was immediately assessed. By decree of the tsar from Tobolsk, the "boyar son" Ivan Shulgin was sent to the banks of Nitsa, who began the construction of a metallurgical plant. Already in 1630 the first 63 pounds of pure iron were received in the Urals. Of these, 20 pishchals, 2 anchors and nails were made. This is how the progenitor of the entire Ural industry arose.

However, until the end of the 17th century, the Urals were still too remote and sparsely populated. Only at the very end of this century, in 1696, Peter I ordered to begin regular geological exploration of the Ural ore - "where exactly is the best stone magnet and good iron ore."

Already in 1700, on the banks of the Neiva River (the source of the already mentioned river Nitsa), the Nevyansk Blast Furnace and Iron Works was built. The following year, a similar plant was built on the site of the modern city of Kamensk-Uralsky. In 1704, 150 versts to the north, a state-owned metallurgical plant appeared in Alapaevsk.

In 1723, the Yekaterinburg state-owned plant was built, which laid the foundation for the formation of the future industrial center of the Urals, the city of Yekaterinburg. In that year, two blast furnaces operated at the plant, producing 88 thousand poods of cast iron per year, and foundries, producing 32 thousand poods of iron per year - that is, only one Ural plant produced the same amount of iron as the whole of Russia produced a century ago, on the eve of Troubled time . In total, 318 workers worked at the Yekaterinburg plant at the end of the reign of Peter I, `of whom 113 were employed directly in production, the rest in auxiliary work.

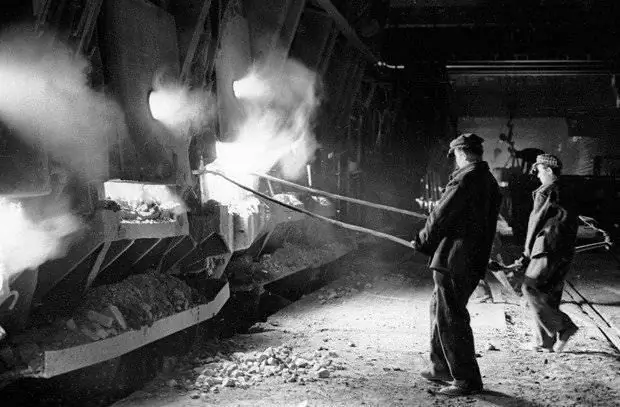

Nevyansk plant, 1935

The Urals turned out to be an ideal place for a metallurgical base. By the beginning of the 18th century, it was already sufficiently populated to provide new factories with labor. The Ural Mountains contained rich deposits of high-quality ores - iron, copper and silver, close to the surface. Numerous deep rivers made it relatively easy to use water as a driving force - this was required primarily for the functioning of large forging hammers and blast bellows, which pumped air into blast furnaces for efficient smelting.

Another important development factor was the Ural forests, which made it possible to cheaply and massively procure charcoal. The technologies of that time required up to 40 cubic meters of wood for the smelting of one ton of iron, which was converted into charcoal by special burning.

Until the end of the 18th century, coal was not used in the production of metals, since, unlike wood coal, it contains considerable amounts of impurities, primarily phosphorus and sulfur, which completely killed the quality of the smelted metal. Therefore, the metallurgical production of that time required huge volumes of wood.

It was the lack of a sufficient amount of wood of the required species that did not allow at that time, for example, England to establish its own mass production of metals. The Urals with its dense forests were devoid of these shortcomings.

Therefore, in the first 12 years of the 18th century alone, more than 20 new metallurgical plants appeared here. Most of them are located on the Chusovaya, Iset, Tagil and Neiva rivers. By the middle of the century, 24 more plants will be built here, which will turn the Urals into the largest metallurgical complex on the planet of that time in terms of the number of large enterprises, factory workers and the volume of metal smelting.

In the 18th century, 38 new cities and settlements will emerge in the Urals around metallurgical plants. Taking into account the factory workers, the urban population of the Urals will then amount to 14-16%, this is the highest urban population density in Russia and one of the highest in the world of that century.

Already in 1750, Russia had 72 "iron" and 29 copper smelters. They smelted 32 thousand tons of pig iron a year (while the factories of Great Britain - only 21 thousand tons) and 800 tons of copper.

Alexandria state plant, early XX century

By the way, it was in the middle of the 18th century in Russia, in connection with metallurgical production, which then required massive deforestation, that the first "ecological" law was adopted - the daughter of Peter I, Empress Elizabeth issued a decree "to protect forests from destruction" to close all metallurgical factories within a radius of two hundred versts from Moscow and move them east.

Thanks to the construction started by Peter I, the Urals became the key economic region of the country in just half a century. In the 18th century, he produced 81% of all Russian iron and 95% of all copper in Russia. Thanks to the factories of the Urals, our country not only got rid of the centuries-old iron deficit and expensive purchases of metals abroad, but also began to massively export Russian steel and copper to European countries.

Iron Age of Russia

The war with Sweden will deprive Russia of the previous supplies of high-quality metal from this country and at the same time will require a lot of iron and copper for the army and navy. But the new plants in the Urals will not only help overcome the shortage of its own metal - already in 1714 Russia will begin to sell its iron abroad. In that year, 13 tons of Russian iron were sold to England for the first time, in 1715 they already sold 45 and a half tons, and in 1716 - 74 tons of Russian iron.

Tata Steel Works, Scunthorpe, England

In 1715, Dutch merchants, who had previously brought metal to Russia, exported 2,846 poods of Russian "rod" iron from Arkhangelsk. In 1716, the export of metal from St. Petersburg began for the first time - that year, British ships exported 2,140 poods of iron from the new capital of the Russian Empire. This is how the penetration of Russian metal into the European market began.

Then the main source of iron and copper for the countries of Europe was Sweden. Initially, the Swedes were not too afraid of Russian competition, for example, in the 20s of the 18th century, on the English market, the largest in Europe, Swedish iron accounted for 76% of all sales, and Russian - only 2%.

However, as the Urals developed, the export of Russian iron grew steadily. During the 20s of the 18th century, it grew from 590 to 2540 tons annually. Iron sales from Russia to Europe grew every decade, so in the 40s of the 18th century, on average, from 4 to 5 thousand tons were exported per year, and in the 90s of the same century, Russian exports increased almost tenfold, to 45 thousand tons of metal annually.

Already in the 70s of the 18th century, the volume of deliveries of Russian iron to England exceeded those of Sweden. At the same time, the Swedes initially had great competitive advantages. Their metallurgical industry was much older than the Russian one, and the natural qualities of Swedish ores, especially in the Dannemura mines, famous throughout Europe, were higher than those in the Urals.

But the most important thing is that the richest mines in Sweden were located not far from seaports, which greatly facilitated and reduced the cost of logistics. While the location of the Urals in the middle of the Eurasian continent made the transportation of Russian metal a very difficult task.

Bulk transportation of metal could be provided exclusively by water transport. The barge, loaded with Ural iron, set sail in April and only reached St. Petersburg in the fall.

The way to Europe of Russian metal began in the tributaries of the Kama on the western slopes of the Urals. Further downstream, from Perm to the confluence of the Kama with the Volga, the most difficult part of the path began here - up to Rybinsk. The movement of river vessels against the current was provided by barge haulers. They dragged a cargo ship from Simbirsk to Rybinsk for one and a half to two months.

The “Mariinsky water system” began from Rybinsk; with the help of small rivers and artificial canals, it connected the Volga basin with St. Petersburg through the White, Ladoga and Onega lakes. Petersburg at that time was not only the administrative capital, but also the main economic center of the country - the largest port in Russia, through which the main flow of imports and exports went.

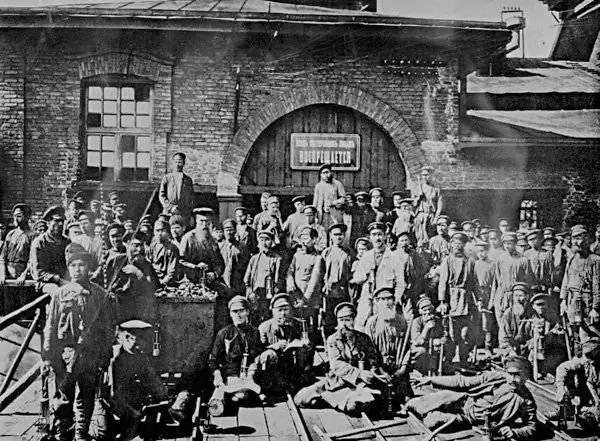

Miners before descending into a mine at the Lugansk plant

Despite such difficulties with logistics, Russian metal remained competitive in the foreign market. Selling prices for export "strip iron" in Russia in the 20s and 70s of the 18th century were stable - from 60 to 80 kopecks per pood. By the end of the century, prices had risen to 1 ruble 11 kopecks, but the ruble rate fell at that time, which again did not lead to significant changes in foreign exchange prices for iron from Russia.

At that time, more than 80% of Russian export iron was bought by the British. However, from the middle of the 18th century, supplies of Russian metal to France and Italy began. On the eve of the French Revolution, Paris annually bought an average of 1,600 tons of iron from Russia. At the same time, about 800 tons of iron per year were exported from St. Petersburg to Italy by ships around all of Europe.

In 1782, the export of iron alone from Russia reached 60 thousand tons, giving revenue over 5 million rubles. Together with the revenues from exports to the East and West of Russian copper and products from Russian metal, this accounted for a fifth of the total value of all our country's exports that year.

During the 18th century, copper production in Russia increased more than 30 times. The closest global competitor in copper production - Sweden - by the end of the century lagged behind our country in terms of production by three times.

Two-thirds of the copper produced in Russia went to the treasury - this metal was especially important in military production. The remaining third went to the domestic market and for export. Most of Russian copper exports then went to France - for example, in the 60s of the 18th century, French merchants annually exported over 100 tons of copper from the St. Petersburg port.

For most of the 18th century, Russia was the largest metal producer on our planet and its leading exporter in Europe. For the first time, our country supplied to the foreign market not only raw materials, but also significant volumes of products of complex, high-tech production for that era.

As of 1769, 159 iron and copper smelters were operating in Russia. In the Urals, the world's largest blast furnaces, up to 13 meters high and 4 meters in diameter, were built with powerful blowers driven by a water wheel. By the end of the 18th century, the average productivity of the Ural blast furnace reached 90 thousand poods of cast iron per year, which was one and a half times higher than the most modern domain of England at that time.

It was this developed metallurgical base that ensured an unprecedented rise in the power and political significance of the Russian Empire in the 18th century. True, these achievements were based on serf labor - according to the lists of the Berg Collegium (created by Peter I, the highest body of the empire for the management of the mining industry), over 60% of all workers at metallurgical plants in Russia were serfs, "assigned" and "purchased" peasants - that is, forced people, which were "attributed" to the factories by tsarist decrees, or purchased for work by the factory administration.

End of the Russian Iron Age

At the very beginning of the 19th century, Russia was still the world leader in the production of metals. The Urals annually produced about 12 million poods of pig iron, while the closest competitors - metallurgical plants in England - smelted no more than 11 million poods a year. The abundance of metal, as a base for military production, became one of the reasons that Russia not only withstood, but also won in the course of the Napoleonic wars.

However, it was at the beginning of the 19th century that a real technological revolution took place in metallurgy, which Russia, in contrast to successful wars, lost. As already mentioned, previously all metal was smelted exclusively on charcoal; existing technologies did not allow obtaining high-quality iron using coal.

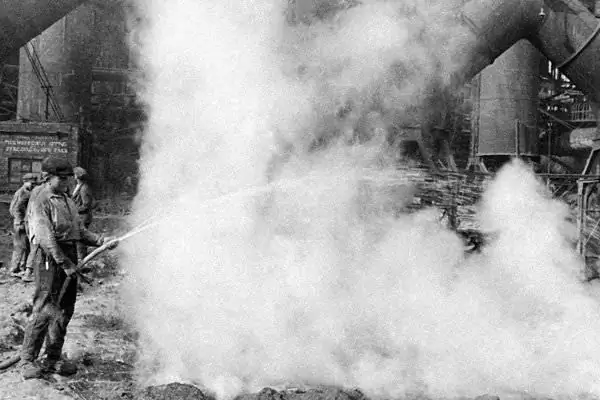

Putting out a fire in the yard of a metallurgical plant in Yuzovka, Donetsk region, 1930. Photo: Georgy Zelma / RIA Novosti

The first more or less successful experiments with the smelting of pig iron on coal took place in England at the beginning of the 18th century. The British Isles lacked their own timber as a raw material for charcoal, but coal was in abundance. The search for the correct technology for smelting high-quality metal on coal took almost the entire 18th century and by the beginning of the next century were crowned with success.

And this gave an explosive growth in the production of metals in England. In the forty years after the end of the Napoleonic wars, Russia increased its production of metals by less than two times, while England during the same time increased the production of pig iron by 24 times - if in 1860 Russian production barely reached 18 million poods of pig iron, then in the British Isles for that the same year produced 13 times more, 240 million poods.

It cannot be said that during this period the industrial technologies of serf Russia stood still. There were some achievements. In the same months, when the guards officers were preparing the performance of the "Decembrists" in St. Petersburg, not far from Petrozavodsk, at the Alexandrovsky State Plant, the first rolling mills for making iron were being prepared for launch (the first in Russia and one of the first in the world).

In 1836, just a few years behind the advanced technologies of England at the Vyksa metallurgical plant in the Nizhny Novgorod province, the first experiments of "hot blast" were carried out - when pre-heated air is pumped into a blast furnace, which significantly saves coal consumption. In the same year, the first in Russia experiments of "puddling" were carried out at the factories of the Urals - if earlier ore was melted mixed with coal, then according to the new technology of "puddling" cast iron was obtained in a special furnace without contact with fuel. It is curious that the very principle of such metal smelting for the first time in the history of mankind was described in China two centuries before our era, and was rediscovered in England at the end of the 18th century.

Already in 1857, exactly one year after the invention of this technology in England, in the Urals, specialists from the Vsevolodo-Vilvensky plant carried out the first experiments of the "Bessemer" method of producing steel from cast iron by blowing compressed air through it. In 1859, Russian engineer Vasily Pyatov constructed the world's first rolling mill for armor. Prior to that, thick armor plates were obtained by forcing thinner armor plates together, and Pyatov's technology made it possible to obtain solid armor plates of a higher quality.

However, individual successes did not compensate for the systemic lag. By the middle of the 19th century, all metallurgy in Russia was still based on serf labor and charcoal. It is significant that even the armored rolling mill, invented in Russia, was widely introduced into the British industry for several years, and remained an experimental production for a long time at home.

At a metallurgical plant in the Donetsk region, 1934. Photo: Georgy Zelma / RIA Novosti

By 1850, in Russia pig iron per capita was produced just over 4 kilograms, while in France over 11 kilograms, and in England over 18 kilograms. Such a lag in the metallurgical base predetermined the military-economic lag of Russia, in particular, it did not allow to switch to the steam fleet in time, which in turn led to the defeat of our country in the Crimean War. In 1855-56, numerous British and French steamers dominated the Baltic, the Black and Azov Seas.

From the middle of the 19th century, Russia again turned from an exporter of metal into a buyer. If in the 70s of the 18th century up to 80% of Russian iron was exported, then in 1800 only 30% of the produced iron was exported, in the second decade of the 19th century - no more than 25%. At the beginning of the reign of Emperor Nicholas I, the country exported less than 20% of the metal produced, and at the end of the reign, exports fell to 7%.

The massive railway construction that began then again gave rise to the iron deficiency forgotten for a century and a half in the country. Russian factories could no longer cope with the increased demand for metal. If in 1851 Russia bought 31,680 tons of cast iron, iron and steel abroad, then over the next 15 years such imports increased almost 10 times, reaching 312 thousand tons in 1867. By 1881, when the "Narodnaya Volya" killed Tsar Alexander II, the Russian Empire was buying 470 thousand tons of metal abroad. Over three decades, imports of cast iron, iron and steel from abroad have grown 15 times.

It is significant that out of 11,362,481 rubles 94 kopecks received by the tsarist government from the United States for the sale of Alaska 1,0972238 rubles, 4 kopecks (that is, 97%) were spent on the purchase of equipment abroad for railways under construction in Russia, primarily a huge number of rails and other metal products … The money for Alaska was spent on imported rails for two railways from Moscow to Kiev and from Moscow to Tambov.

In the 60-80s of the XIX century, almost 60% of the metal consumed in the country was bought abroad. The reason was already the glaring technological backwardness of Russian metallurgy.

Until the last decade of the 19th century, two-thirds of the pig iron in Russia was still produced on charcoal. Only by 1900 the amount of pig iron smelted on coal will exceed the amount obtained from the monstrous mass of burnt wood.

Very slowly, in contrast to the Western European countries of those years, new technologies were introduced. So, in 1885, out of 195 blast furnaces in Russia, 88 were still on cold blast, that is, on the technology of the beginning of the 19th century. But even in 1900, such furnaces, with almost a century lag in the technological process, still accounted for 10% of the blast furnaces of the Russian Empire.

In 1870, 425 new "puddling" furnaces and 924 "chimneys" were operating in the country using the old technology of the beginning of the century. And only by the end of the 19th century, the number of "puddling" furnaces will exceed the number of "blast furnaces" created by the hands of serfs.

Donbass instead of the Urals

Since the times of Peter the Great, for almost a century and a half, the Urals have remained the main center for the production of Russian metal. But by the beginning of the 20th century, at the other end of the empire, it had a powerful competitor, thanks to which Russia was able to at least partially overcome the lag behind the metallurgy of Western countries.

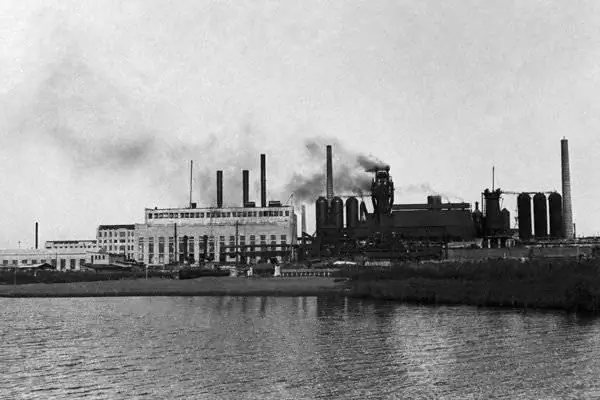

Metallurgical plant "Azovstal", Mariupol, 1990. Photo: TASS

If the industry of the Urals was based on charcoal, then the new industrial region originally arose precisely on the deposits of coal. Surprisingly, here, too, Tsar Peter I became the ancestor. Returning from the first Azov campaign in 1696, in the area of the modern city of Shakhty near the borders of Donbass, he examined samples of a well-burning black stone, the deposits of which in this area almost came to the surface.

“This mineral, if not for us, then for our descendants will be extremely useful,” the words of the reformer tsar preserved the documents. Already in 1721, at the direction of Peter I, the Kostroma peasant Grigory Kapustin conducted the first search for coal deposits in the future Donbass.

However, they were able to master the first smelting of ore with coal and begin to populate the steppes of the Azov region only by the end of the 18th century. In 1795, Empress Catherine II signed a decree "On the establishment of a foundry in the Donetsk district by the Lugan River and on the establishment of the removal of coal found in that country." This plant, whose main task was the production of cast-iron cannons for the ships of the Black Sea Fleet, laid the foundation for the modern city of Lugansk.

Workers for the Lugansk plant came from Karelia, from the cannon and metallurgical factories of Petrozavodsk, and from the metallurgical plant founded by Peter I in Lipetsk (there, over a century, the surrounding forests were cut down for charcoal for the blast furnace and production became unprofitable). It was these settlers who laid the foundation for the proletariat of the future Donbass.

In April 1796, the first coal mine in the history of Russia was put into operation for the Lugansk plant. It was located in the Lisichya gully and the village of miners eventually became the city of Lisichansk. In 1799, under the guidance of craftsmen hired in England at the Lugansk plant, the first experimental smelting of metal on local coal from local ore began in Russia.

The problem of the plant was a very high production cost compared to the old serf factories of the Urals. Only the high quality of the smelted metal and the need to supply the Black Sea Fleet with cannons and cannonballs saved the plant from closing.

The rebirth of the Donetsk industrial center of Russia began in the 60s of the XIX century, when, in addition to military products, a lot of steel rails were required for the construction of railways. It is curious that the economic calculations and geological surveys of coal and ore for future Donbass factories were then done by Apollo Mevius, a mining engineer from Tomsk, on the paternal side he came from the descendants of Martin Luther, the founder of European Protestantism, who moved to Russia, and on the maternal side, from the Siberian Cossacks. schismatics.

At the very end of the 60s of the XIX century, the right to build industrial enterprises in the Donbass (then it was part of the Yekaterinoslav province) was received by a friend of Tsar Alexander II, Prince Sergei Kochubei, a descendant of the Crimean Murza, who had once deserted to the Zaporozhye Cossacks. But the Russian prince of Cossack-Tatar origin was most of all fond of sea yachts, and in order not to waste time on boring construction business, in 1869, for a huge sum of 20 thousand pounds sterling at that time, he sold all the rights received from the Russian government for the construction and development of mineral resources to the British industrialist from Wales John James Hughes.

John Hughes (or as he was called in Russian documents of those years - Hughes) was not only a capitalist, but also an engineer-inventor who got rich on the creation of new models of artillery and ship armor for the British Navy. In 1869, an Englishman ventured to buy the rights to build a metallurgical plant in the then undeveloped and sparsely populated Novorossia. I took a chance and made the right decision.

Jorn Hughes corporation was called "Novorossiysk Society of Coal, Iron and Rail Production". Less than three years later, in 1872, a new plant, built next to rich coal deposits near the village of Aleksandrovka, smelted the first batch of pig iron. The village is quickly turning into a workers' settlement Yuzovka, named after the British owner. The modern city of Donetsk has its ancestry from this village.

Following the factories in the future Donetsk, two huge metallurgical plants appear in Mariupol. One plant was built by engineers from the United States and belonged to the Nikopol-Mariupol Mining and Metallurgical Society, controlled by French, German and American capital. However, according to rumors, the then all-powerful Minister of Finance of the Russian Empire, Count Witte, also had a financial interest in this enterprise. The second of the metallurgical giants under construction in Mariupol of those years belonged to the Belgian company Providence.

Unlike the old plants in the Urals, the new metallurgical plants in Donbass were originally built as very large by the standards of that time, with the most modern equipment purchased abroad. The commissioning of these giants almost immediately changed the whole picture of Russian metallurgy.

The production of cast iron and iron for the years 1895-1900 doubled throughout the country as a whole, while in Novorossia it almost quadrupled over these 5 years. Donbass quickly replaced the Urals as the main metallurgical center - if in the 70s of the XIX century the Ural factories produced 67% of all Russian metal, and Donetsk only 0.1% (one tenth of a percent), then by 1900 the share of the Urals in the production of metals decreased up to 28%, and the share of Donbass reached 51%.

Non-Russian Russian metal

On the eve of the 20th century, Donbass provided more than half of all the metal of the Russian Empire. Production growth was significant, but still lagged behind the leading European countries. So, by the end of the 19th century, Russia produced 17 kilograms of metals per capita per year, while Germany - 101 kilograms, and England - 142 kilograms.

With the richest natural resources, Russia then gave only 5, 5% of world pig iron production. In 1897, 112 million poods were produced at Russian factories, and almost 52 million poods were purchased abroad.

True, that year our country was the leader on the planet in terms of production and export of manganese ores required for the production of high-quality steel. In 1897, 22 million poods of this ore were mined in Russia, which accounted for almost half of all world production. Manganese ore was then mined in the Transcaucasus near the city of Chiatura in the very center of modern Georgia, and in the area of the city of Nikopol in the territory of modern Dnepropetrovsk region.

However, by the beginning of the 20th century, the Russian Empire was seriously lagging behind in the production of copper, a very important metal for many military and civilian technologies of that time. Back at the beginning of the 19th century, our country was one of the leading exporters of copper to Europe; in the first quarter of a century, 292 thousand poods of Ural copper were sold abroad. At that time, the entire bronze industry of France worked on copper from the Urals.

Workers attend the ceremonial launch of the blast furnace of the Alapaevsk Metallurgical Plant, 2011. Photo: Pavel Lisitsyn / RIA Novosti

But by the end of the century, Russia itself had to buy imported copper, since the country produced only 2.3% of the world production of this metal. Over the last decade of the 19th century, the export of Russian copper amounted to less than 2 thousand poods, while over 831 thousand poods of this metal were imported from abroad.

The situation was even worse with the extraction of zinc and lead, which are equally important metals for the technologies of the early 20th century. Despite the wealth of its own subsoil, their production in Russia then amounted to hundredths of a percent in world production (zinc - 0.017%, lead - 0.05%), and all the needs of Russian industry were satisfied entirely through imports.

The second vice of Russian metallurgy was the constantly growing dominance of foreign capital. If in 1890 foreigners owned 58% of all capital in the metallurgical industry in Russia, then in 1900 their share had already grown to 70%.

It is no coincidence that at the dawn of the 20th century, the second city in Russia after the capital of St.foreign capital, and Mariupol was not only one of the largest centers of metallurgy, but also the main trade port for a vast industrial area with factories and mines in Donbass.

In the first place among the foreign owners of Russian metal were the Belgians and the French (it was they who controlled, for example, the production of manganese ores in Russia), followed by the Germans, then the British. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Russian economist Pavel Ol calculated that the share of foreign capital in the mining industry at that time was 91%, and in metal processing - 42%.

For example, by 1907, 75% of all copper production in Russia was controlled by German banks through the Copper syndicate. On the eve of the First World War, the situation only worsened - by 1914, German capital controlled 94% of Russian copper production.

But it was thanks to large foreign investments that the metallurgical and mining industry of Russia showed impressive growth in the 25 years before the First World War - the production of pig iron increased almost 8 times, the production of coal increased 8 times, and the production of iron and steel increased 7 times.

In 1913, buying a kilogram of iron in Russia on the market cost an average of 10-11 kopecks. In modern prices, this is about 120 rubles, at least twice as expensive as modern retail prices for metal.

In 1913, Russian metallurgy ranked 4th on the planet and in key indicators was approximately equal to the French, but still lagged behind the most developed countries of the world. In that reference year, Russia smelted steel six times less than the United States, three times less than Germany and two times less than England. At the same time, the lion's share of the ore and almost half of the metal in Russia belonged to foreigners.