- Author Matthew Elmers elmers@military-review.com.

- Public 2023-12-16 21:49.

- Last modified 2025-01-24 09:17.

Preparing for a big war

In the first part of the material on the aluminum industry and its impact on the military potential of the Soviet Union, it was said that the country was seriously lagging behind Germany. In 1941, the Nazi industry was more than three times ahead of the Soviet in this parameter. Moreover, even their own calculations within the framework of the MP-1 mobilization plan, which date back to June 17, 1938 (approved by the Defense Committee under the Council of People's Commissars), assumed that the country would need about 131.8 thousand tons of aluminum in case of war. And by 1941, in reality, the Soviet Union was capable of producing no more than 100 thousand tons of "winged metal", and this, of course, without taking into account the loss of the western territories, where the main enterprises of non-ferrous metallurgy were located.

The aviation industry was the most sensitive to the aluminum deficit, and the Council of People's Commissars developed a number of measures to partially meet the growing needs of the People's Commissariat for Aviation Industry. In 1941, the shortage was supposed to be closed by using the return of light metals (34 thousand tons), the introduction of refined wood (15 thousand tons) into the design of aircraft, the production of magnesium alloys (4 thousand tons) and through banal savings (18 thousand tons). tons). This, by the way, was a consequence of the increased mobilization appetites of the Soviet Union: by 1942 it was planned to use not 131, 8 thousand tons of aluminum, but more than 175 thousand tons. In addition to the quantitative increase in the production of aluminum, methods of qualitative improvement of alloys based on the "winged metal" were envisaged in advance in the country. Duralumin aircraft were initially more repaired and painted in the army than they were flying, which was a consequence of the low corrosion resistance of the alloy. Over time, the Aviakhim plant developed a method for cladding duralumin with pure aluminum (which, in turn, was covered in air with a strong protective oxide film), and since 1932 this technique has become mandatory for the entire Soviet aviation industry.

"Aluminum famine" negatively affected the quality of domestic aircraft not only of the light-engine class of the U-2 and UT-2 types, but also of the Yak-7 and LaGG-3 fighters. For example, the Yak-7 fighter was an airplane with a wooden wing and smooth plywood fuselage skin. The tail part of the hull, rudders and ailerons were covered with canvas. Only the engine hood and side hatches of the aircraft nose were made of duralumin. Moreover, one of the main combat fighters of the war period, the LaGG-3, was generally all-wood. The load-bearing elements of its structure were made of the so-called delta-wood. The pilots sarcastically deciphered the abbreviation "LaGG" as "lacquered guaranteed coffin." Nevertheless, 6,528 such aircraft were produced, including at the aircraft factories of Leningrad, and they actively participated in hostilities. According to the military historian A. A. Help, these fighters were originally "doomed to yield to the German aluminum Me-109, which by 1941 approached the speed of 600 km / h."

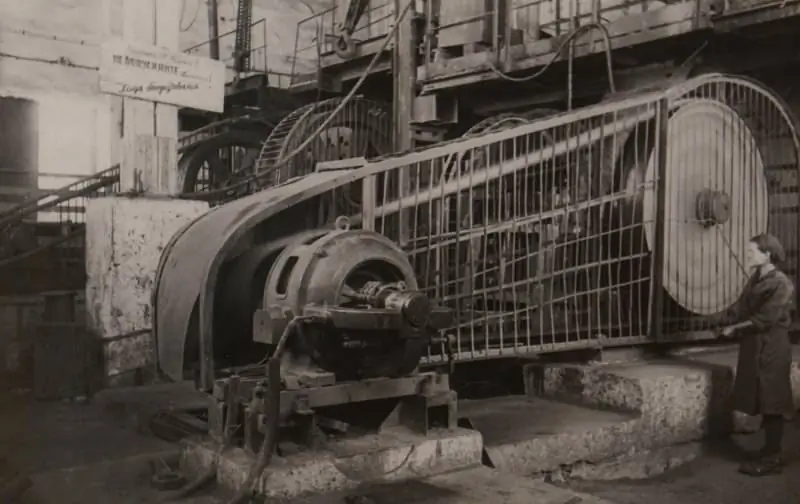

Alloys on an aluminum base, so necessary for aviation, in the USSR by the beginning of the war were smelted by three plants: Voroshilov in Leningrad, Moscow No. 95 and the Stupino light alloy plant No. 150 built in 1940. During the construction of the latter, they actively turned to the Americans for help. In 1935, a delegation led by Andrei Tupolev went to the United States, where it turned out that large sheets of duralumin 2, 5 meters by 7 meters are widely used in overseas aircraft construction. In the USSR, by that time they could not make a sheet more than 1x4 meters - such technological standards have existed since 1922. Naturally, the government asked Alcoa to provide multi-roll mills for the production of similar duralumin sheets, but the answer was no. Didn't sell the mills to Alcoa - this is how the old business partner of the Soviet Union, Henry Ford, will. His company and several other similar ones in the United States supplied several large rolling mills for aluminum alloys to the USSR in the late 1930s. As a result, the Stupino plant alone in 1940 produced 4191 tons of high-quality duralumin rolled products.

The thirteenth element of victory

The largest loss of the beginning of the Great Patriotic War for the aluminum industry was the Dneprovsky aluminum plant. In mid-August, they tried to detain the German tanks rushing to Zaporozhye by partially destroying the Dnieper Hydroelectric Power Station, which led to numerous casualties both among the occupiers and among the Red Army and civilians. The evacuation of the Dneprovsky aluminum smelter, the largest plant among its kind in Europe, was handled by high-ranking officials right next to the Germans: Chief Engineer of Glavaluminiya A. A. The evacuation under constant enemy fire (the Nazis were on the other side of the Dnieper) ended on September 16, 1941, when the last of two thousand wagons with equipment was sent to the east. The Germans did not manage to organize the production of aluminum at the Zaporozhye enterprise until the very moment of exile. According to a similar scenario, the Volkhov aluminum and Tikhvin alumina refineries were evacuated.

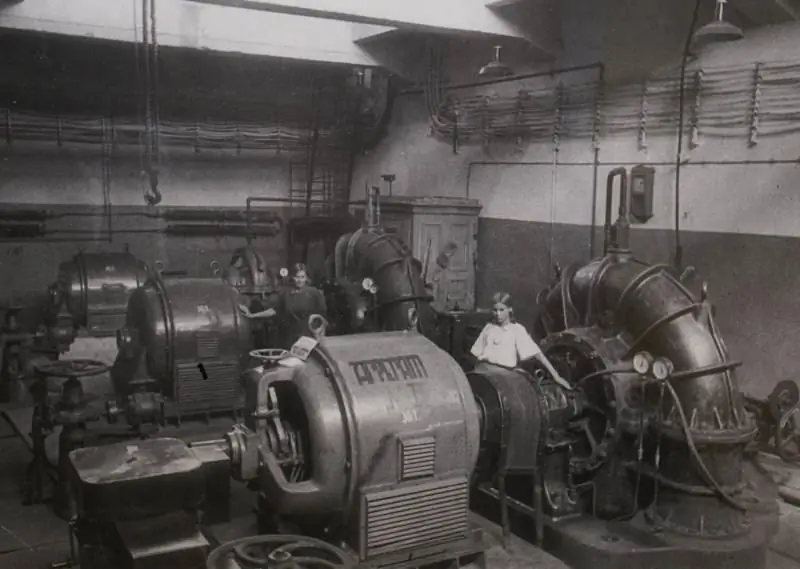

In the fall of 1941, the production of duralumin rolled products ceased and was restored only by May of the following year. Now production was based only at two enterprises: plant no. 95 in Verkhnyaya Salda and plant no. 150 at the Kuntsevo station. Naturally, due to a temporary stop, the volume of production of all-metal aircraft sank, albeit slightly, from 3404 copies from 1940 to 3196 winged aircraft in 1941. But since 1942, the volume of duralumin aircraft production has been steadily growing. Formally, the Soviet aviation industry managed to overcome the acute shortage of duralumin by the summer of 1944 - it was then that the volume of aircraft production stabilized. With regard to fighters, this could be observed during Operation Bagration in Belarus, when aircraft designed by S. A. Lavochkin La-7. Most of its load-bearing elements were made of light metal alloys. The fighter was superior to its main enemy, the FW-190A, in speed, climb rate and maneuverability. And if in 1942 the growth in aircraft production was explained by the commissioning of capacities evacuated from west to east, then in 1943 aluminum plants appeared in the country, which had not existed before. This year it was possible to commission the construction of the Bogoslovsky aluminum plant in the Sverdlovsk region and the Novokuznetsk aluminum plant in the Kemerovo region. Specialists from the previously evacuated Volkhov Aluminum and Tikhvin Alumina Plants provided enormous help in organizing the production of aluminum at these enterprises. Regarding the Theological Aluminum Plant, it should be said that the first aluminum smelting was carried out only on a significant day - May 9, 1945. The first stage of the Novokuznetsk plant was launched back in January 1943. In the same year, aluminum smelting in the USSR exceeded the pre-war level by 4%. For example, only the Ural Aluminum Plant (UAZ) in 1943 produced 5.5 times more aluminum than before the war.

Obviously, the deficit of domestic aluminum was overcome not without the help of supplies from the United States under the Lend-Lease program. So, back in July 1941, when receiving in the Kremlin the personal representative of the American President G. Hopkins, Joseph Stalin named high-octane gasoline and aluminum for the production of aircraft among the most necessary types of assistance from the United States. In total, the USA, Great Britain and Canada supplied about 327 thousand tons of primary aluminum. Is it a lot or a little? On the one hand, not much: the United States alone, within the framework of the Lend-Lease, sent to the USSR 388 thousand tons of refined copper, a much more scarce raw material. On the other hand, supplies from abroad accounted for 125% of the level of aluminum production in wartime in the Soviet Union.

Progress in the production of aluminum during the Great Patriotic War was observed not only in terms of increasing production volumes, but also in reducing energy consumption for smelting. So, in 1943, the USSR mastered the technology of casting aluminum in gas furnaces, which seriously reduced the dependence of non-ferrous metallurgy enterprises on electricity supplies. In the same year, the technique of continuous casting of duralumin began to be widely used. And a year earlier, for the first time in the history of industry at the Ural plant, the current output of aluminum exceeded 60 grams of metal per 1 kilowatt-hour of electricity at the required rate of 56 grams. This was one of the reasons for the brilliant achievement of 1944 - UAZ saved 70 million kilowatt-hours of electricity. I think it would be pointless to talk about what this meant for the mobilized industry of the Soviet Union.