- Author Matthew Elmers elmers@military-review.com.

- Public 2023-12-16 21:49.

- Last modified 2025-01-24 09:17.

“Oh, West is West, East is East, and they will not leave their places, Until Heaven and Earth appear at the Last Judgment of the Lord.

But there is no East, and there is no West, that the tribe, homeland, clan, If the strong with the strong stands face to face at the edge of the earth."

(R. Kipling. Ballad about West and East. Translation by E. Polonskaya)

The question of where the first knights appeared (first of all with certain weapons, traditions, emblems, emblems) has always occupied the minds of specialists in the field of knightly weapons. And, really - where? In England, where they are depicted on the "Bayesian canvas", in Charlemagne's France, where they were depicted in the psalteries from St. Galen, whether they were the Yarls of Scandinavia, or these are Roman, or rather, Sarmatian cataphracts, hired by the same Romans to serve in Britain. Or maybe they appeared in the East, where already in 620 the riders were dressed in chain mail armor literally from head to toe [Robinson R. Armor of the peoples of the East. The history of defensive weapons. Moscow: 2006, p. 34.].

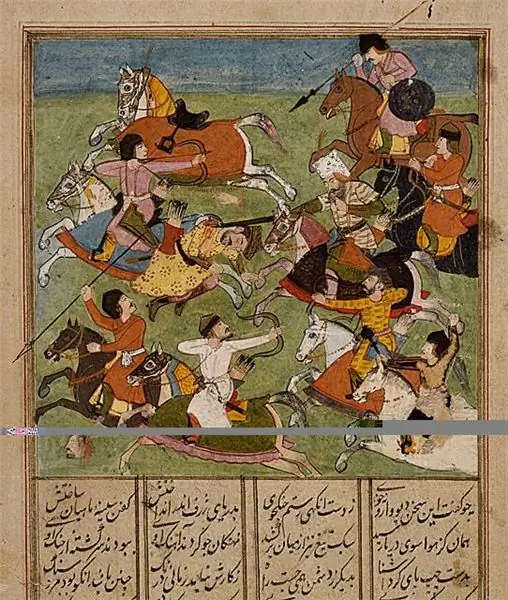

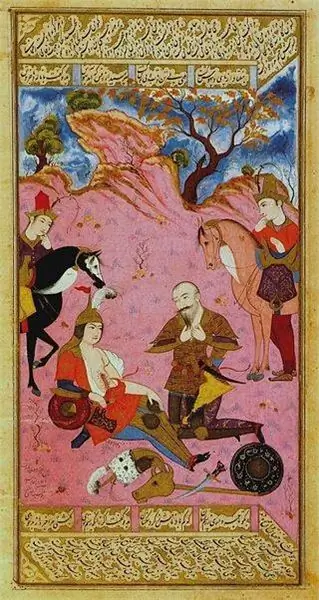

Battle scene and text from "Shahnameh" by Ferdowsi, early 17th century. India, Delhi. Pay attention to the horse blankets and the fact that the armor of the riders is hidden under the clothes. (Los Angeles Regional Museum of Art)

In the Central Asian Penjikent, frescoes have survived, which show warriors in chain mail, which appeared in Western Europe only four centuries later! In addition, the Sogdians, the inhabitants of the interfluve between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, already in the 10th century used several types of lamellar shells, among which one, due to the size of its plates, was called “palm wide” [Nicolle D. Sons of Attila (Central Asian warriors, 6th to 7th centuries AD) // Military illustrated №86. R. 30-31].

Horsemen, who fought in armor covered with metal plates, existed in the 9th-11th centuries in the states of the mighty Arab Caliphate. Poets did not spare epithets, describing the armor of these warriors as "consisting of many mirrors", and Arab historians also added that their protective equipment looked "like Byzantine". We have an idea of the latter on the basis of ancient Russian icon painting and surviving miniatures from the "Review of History" by John Skilitsa, in which horsemen are shown dressed in armor made of polished metal plates that used to sparkle brightly in the sun [Nicolle D. Armies of the caliphates 862 -1098. L.: Osprey (Men-at-arms series No. 320), 1998. P. 15.].

Miniature from "Review of History" by John Skilitsa. The Bulgarians, led by Tsar Simeon I, defeat the Byzantines. Madrid, National Library of Spain.

We can say that the Near and Middle East in the epoch from the 7th to the 11th century could already boast that their warriors had two sets of protective armor at once - chain and plate armor, which were often used simultaneously, however, unfortunately, this is poorly confirmed illustrative material. Here the consequences of the invasion here, first by the Turkish, and then by the Mongol conquerors, are to blame.

The most famous artifact depicting a rider in armor is a fragment of a wooden shield discovered in the Mug fortress near Samarkand. Moreover, it can be attributed to the XIII century. On him we see armor, representing something like a long-skirted caftan, on which there were shoulder pads and forearms in bracers tightly fitting to it, although both hands were open [Robinson R. Armor … p. 36]. Rashid ad-Din's History of the World, which was written and illustrated in Tabriz in 1306-1312, can also be attributed to the number of noteworthy sources.

On her miniatures, we again see warriors dressed in long armor made of metal scales with multi-colored patterns, obtained by alternating ornamented plates and lacquered leather scales. Helmets have a characteristic rounded top shape with a central point, while their brow section is often additionally reinforced with a metal plate. There are three types of the back of the back: leather, chain mail and quilted, and it falls on the chain mail. In Central and South Persia, as R. Robinson believed, mail armor was predominant.

Persian mace of the 16th century. (Metropolitan Museum, New York)

Warriors from Persia had such an original form of protection as a chain mail cloak, called a zarikh-bektash, but besides it, they could wear armor made of iron plates, covered with velvet on top. In fact, it is an exact copy of the European brigandine, but in an oriental manner [Wise T. Medieval European Armies. Oxford, 1975. P. 28.]. It was customary to protect horses with blankets of quilted cotton fabric [Robinson R. Armor … p. 37].

On miniatures dating back to the XIV century, warriors also wear scaly armor, helmets of simple shape - low, rounded or conical, and have chain mail aventails. Some helmets have earpieces. Plumes are clearly absent, but there are some spikes on the helmets.

Already at the end of the 14th - beginning of the 15th century, tubular bracers of two plates, which converged to the wrist in the form of a cone, were spreading in the East. The legs were covered with knee pads, which were attached directly to the chain mail or they were sewn into the fabric base that protected the thighs. The riders had boots on their feet, and again, leggings made of two curved plates connected to each other on hinges were put on the shins and calves, which is clearly seen in many miniatures dating back to the first third of the 15th century [Wise T. Medieval European Armies / С. 38-39].

Persian "bull-headed mace" of the 19th century. (Length 82.4 cm). (Metropolitan Museum, New York). The hero Rustam fights with a similar mace in Ferdowsi's poem.

Note that English historians very often use such an epic work as Ferdowsi's poem "Shahnameh" as a source. It is known that it was written at the end of the 10th - beginning of the 11th century [It is believed that Ferdowsi completed his poem in the first edition in 994, but the second was completed in 1010.]. We will follow their example and read several passages from it.

Rustam said: “Get my damask sword.

A battle helmet and all my armor;

Arcanum and bow; chain mail for a horse;

A tiger skin caftan for me …

He clothed his shoulders with chain mail of steel, He put on armor, took the weapon of the slash …

And he galloped into the steppe, shining with a shield, Playing with his heavy club.

(Translation by V. Derzhavin)

That is, if we take into account that Ferdowsi described what he saw, then not only Rustam wore chain mail, but the blanket of his horse Raksha was also made of chain mail. The poem tells about it like this:

There was a horse in front of the tent in armor, Listening to the unexpected war.

(Translated by S. Lipkin)

In the "Shahnama" it is emphasized many times (which again testifies that the poem was written by a man who knew the military affairs very well) that the helmet is put on the head before the warrior puts on chain mail. And this means that the Iranian helmets were conical in shape. It was they who were worn before putting on the chain mail, since in this case it slides over its smooth metal surface.

And he got up and girded himself for battle, He took off the golden crown from his head, He put on an Indian damask helmet instead, The mighty camp was clothed with military chain mail.

He took his sword and spear and his club, Like a heavy thunder that strikes in battle.

(Translation by V. Derzhavin)

Bogatyr Rustam in the poem also wears a tiger skin over his chain mail; this is somewhat strange, but for the legendary hero anything is possible. Nevertheless, this stroke is confirmation that in the East, rich robes could be worn over armor.

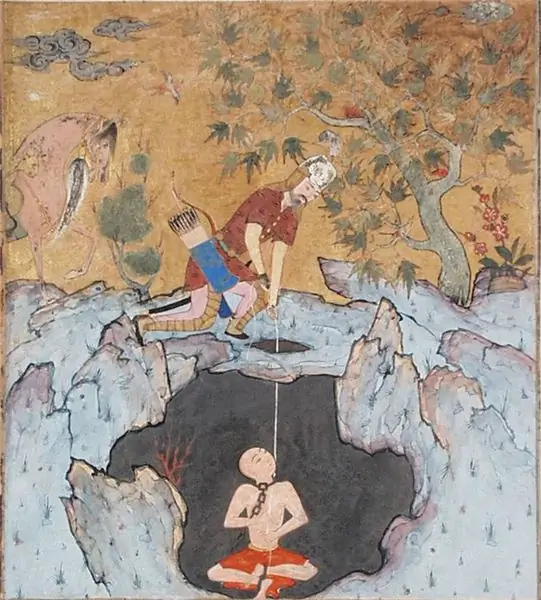

Rustam in a tiger skin caftan rescues Bishwan from prison. Miniature from the poem "Makhname". Iran, Khorasan, 1570 - 1580 (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Rustam, in brocade from Rum and in armor, Instantly was on a horse.

(Translated by S. Lipkin)

It is known that the 1340 Shahnameh manuscript was included in many European and American collections, being divided into parts. But on her miniatures, nevertheless, helmets are visible, with aventails, which completely hide the faces of the soldiers and have only very tiny holes, that is, they protect the face and eyes from arrows. In Eastern Europe, such helmets are also found. They are also found in the 7th century Wendel graves discovered in Sweden.

"Turban helmet" of the 15th century. Iran. (Metropolitan Museum, New York)

In the manuscript "Shahnameh" from Gulistan, miniatures of which belong to the Herat school and were made in 1429, we see such minute details as scaly shoulders worn over chain mail, and some also have the same legguards along with knee pads.

Iranian chain mail armor. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

The Shahnameh manuscript, dating from 1440, is kept in the funds of the British Royal Asiatic Society, and in it, on the miniatures, aventail is visible, covering only the lower part of the face. Again, the scaly aventail is in use, covering the shoulders. Some warriors have armor very similar to those that were used by the ancient Romans and Parthians [Robinson R. Armor … p. 40.] - others are dressed in long-length cloth clothes, and the armor is worn under them.

Bogatyr Rustam (left) sends an arrow into Isfandiyar's eye. Around 1560 Many warriors are covered with chain mail armor with a convex metal cover for the kneecap. Miniature from "Shahnameh". Iran, Shiraz. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Ian Heath, one of the English historians and the author of a number of books translated into Russian in our country, noted that a certain Gazan Khan (who ruled from 1295 to 1304) played an important role in improving weapons production in Persia. Under him, the master gunsmiths who lived in the cities began to receive a salary from the state, but for this they were obliged to supply their products to the Shah's treasury, which allowed him to have from 2,000 to 10,000 different sets of armor per year!

R. Robinson believes that the most popular armor of this time was the so-called huyag - a “corset” made of fabric with metal plates sewn onto it. They could be painted or even enameled. Armor of the Mongolian pattern and armor of local, that is, Iranian forms were used in approximately the same way; the shields of the warriors were small, covered with leather and had four umbons on the outer surface; such shields in Persia appeared already at the end of the XIII century and were used even until the end of the XIX [Robinson R. Armor … S. 40.].

In the USSR, based on the work "Shahnameh" in 1971, at the Tajikfilm film studio, an excellent epic film "The Tale of Rustam" was shot, as well as its sequel "Rustam and Suhrab". Then in 1976 the third part will be released: "The Legend of Siyavush". The costumes of the heroes are quite historical, although they have a lot of purely fantasy exoticism. Here is the hero of the film, Rustam. A real hero, brave, fair and stupid … I forgot that the guilty tongue is cut off along with the head! Well, was it possible to make such speeches in the Shah's palace: “My throne is a saddle, my crown is a helmet, my glory on the field / What is Shah Kavus? The whole world is my power. " It is clear that this was immediately reported to the latter and he sent the hero to the distant border.

It is significant that in the miniatures already at the beginning of the 15th century, about half of the Persian horsemen are riding horses covered with armor. Most often, these are blankets made of "quilted silk", and already known (judging by the miniatures) already in 1420. But who did they belong to? After all, they were sold and bought, exchanged and captured in the form of trophies. Most likely, they could "travel" throughout the then Muslim East! Moreover, in the Turkish cavalry of the Sipahi, the number of riders who had horses in blankets met in the proportion of one rider on a "shell" horse for 50 - 60 riders on "unarmored horses!" [Heath I. Armies … Vol. 2. P. 180.]

Bahram night attack. Miniature from the poem "Shahnameh" 1560 Iran, Shiraz.(Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

All this suggests that the warriors of the East were quite susceptible to foreign influence. Judging by the poem "Shahnameh", even the legendary warriors-pahlavans - heroes of the pre-Muslim era - procured weapons for themselves in a variety of ways and did not consider it reprehensible to dress in the enemy's armor and use his weapons. We constantly come across such a term as "Rumian helmet", that is, "from Rum" - Rome, we are talking about swords from India and the same Rum. That is, Byzantine weapons were apparently highly valued in Iran during the time of Ferdowsi. So already in those years, despite constant wars, there was an intensive arms trade between the countries of the East, which made the warriors of these countries look, converging on the battlefield, like brothers.

Here he is, the worthless and cowardly Shah Kavus, envious of Rustam's glory. He said, however, clever words: "After all, the ancient wisdom does not say for nothing - il the shah kills, or he himself is killed!"

Moreover, it was here, in the East, that the defensive weapons had very ancient roots. So, armor made of leather, with sewn horn or metal scales, was used in India long before the appearance of the Mongols and Arabs on its lands. The same can be said about horse armor, which appeared a very long time ago in China, then Iran, in the Arab states and in Byzantium, that is, when the Europeans did not even dream of having them.

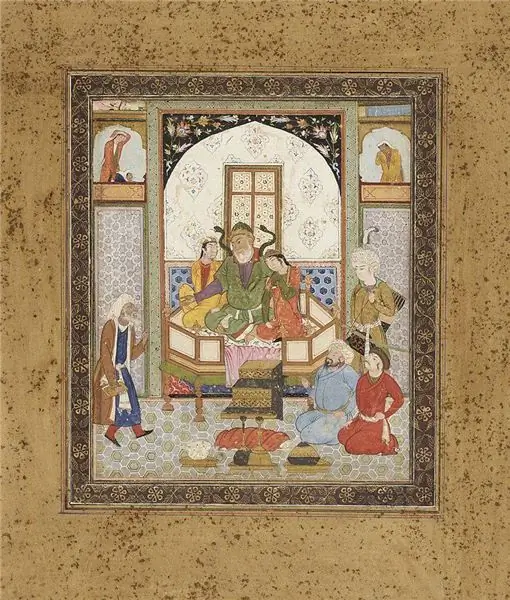

And here is this miniature from the Bukhara manuscript of 1615. It depicts Tsar Zahkhok with his two daughters and … snakes sprouting from his shoulders - a plot from "Shahnameh", which formed the basis of the Soviet film "The Banner of the Blacksmith" (filmed at the Tajikfilm film studio in 1961). (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

It turns out that the institution of chivalry in Asia itself has more ancient roots than in Europe. This conclusion found its definite reflection even in heraldry. So, in the Sassanid state, the feudal lord, having received hereditary flax, received the right to wear his own coat of arms. The Arab historian Kebeh Farrukh, for example, notes that the emblems of the Persian nobility appeared long before the appearance of coats of arms in Europe. Among the heraldic figures named by him there are, for example, such animals as a deer, a lion, a wild boar, a horse, an elephant and a Semurg bird, objects such as a trident and even images of people. Farrukh also refers to the text from the "Shahnameh", where descriptions of images on the banners of the Iranian cavalry are given, and this is just what practically does not differ from the images and emblems on the banners of the knights in Western Europe! [Cm. more details: Farrokh K. Sassanian Elite cavalry 224-642 AD. Oxford Osprey (Elite series # 110), 2005.] And here each warrior, especially if he is leading a detachment, has his own banner, which adorns the symbolic image:

Tukhar replied: “O sir, You see the leader of the squads

Swift Tusa the commander, Who fights to death in formidable battles.

A little further - another banner is burning with fire, And the sun is painted on it.

Behind him Gustakhm, and the knights are visible, And a banner with the image of the moon.

Militant he leads the regiment, A wolf is drawn on a long banner.

The slave is as light as a pearl, Whose silk braids are like resin

Drawn beautifully on the banner.

That is the military banner of Bijan, son of Gibe.

Look, there is a leopard's head on the banner, What makes the lion tremble.

That is the banner of Shidush, a warrior-nobleman, What walks is like a mountain ridge.

Here is Guraza, in his hand is a lasso, The banner depicts a wild boar.

Here are people full of courage jumping, With the image of a buffalo on the banner.

The squad consists of spearmen.

Their leader is the valiant Farhad.

And here is Gudarz, Kishwada, the gray-haired son, On the banner - the lion sparkles gold.

But on the banner is a tiger that looks wildly, Rivkiz the warrior is the lord of the banner.

Nastuh, son of Gudarza, enters into battle

With the banner where the doe is drawn.

Bahram, son of Gudarza, fights fiercely, Depicts the banner of his argali.

(Translated by S. Lipkin)

Rustam-papa kills Sukhrab-son - the plot of many heroic legends, epics and legends. Muin Musavvir. Death of Surkhab. "Shahnameh" 1649 (British Museum, London)

In the East, almost the most ancient form of armor was also worn over the chain mail - a breast and dorsal disk-mirror - that is, a simple metal circle, often with a corrugated surface, fastened with leather belts, crossing the warrior on the back. For example, in India they were worn on quilted armor, again lined with metal plates. But on the miniatures "Shahnameh" from Gulistan, such discs are visible on the soldiers' chest only.

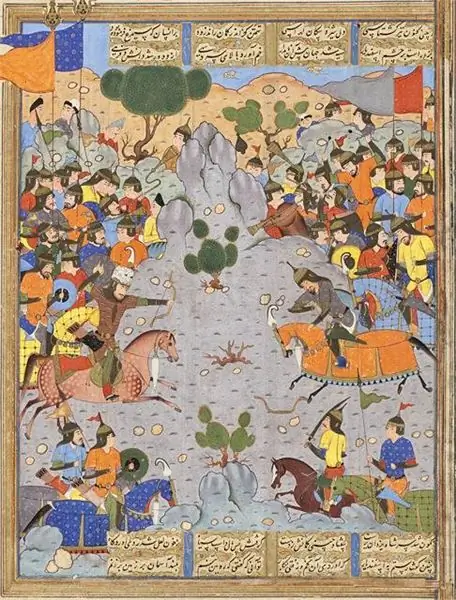

Giv fights Lahhak and Farshidwar. Another miniature from the "Shahnameh", circa 1475 - 1500, in which the equipments of the eastern riders include horse blankets and masks, while the warriors have helmets with headphones, their faces are half closed, there are elbow pads and knee pads. The shield, however, only one of the warriors. (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

That is, the "knights from" Shahnameh "are … really eastern knights, armed in about the same way as their western counterparts in craft, except for the latter tradition of shooting from a galloping horse. And so the flags, and pennants on spears, and various types of armor, for all their originality, were in many ways similar. Moreover, they came to the West from the East through Byzantium and during the Crusades from West to East!