- Author Matthew Elmers elmers@military-review.com.

- Public 2023-12-16 21:49.

- Last modified 2025-01-24 09:17.

In the summer mountains

Somewhere a tree collapsed with a crash -

distant echo.

Matsuo Basho (1644-1694). Translated by A. Dolina

Not so long ago, on the VO, the conversation about Japanese weapons and Japanese armor turned up for the umpteenth time. Again, it was quite surprising to read about armor made of wood and questions about "Japanese varnish". That is, someone somewhere clearly heard the ringing, but … does not know where it is. However, if there is a question, how did Japanese armor differ from all others, then there must be an answer. And this is what will be discussed in this article. Since materials about Japanese armor have already been published on VO, there is no point in repeating them. But to focus on some interesting details, like the same famous varnish, why not?

When you look at Japanese armor up close, the first thing you see is colored cords. The plates underneath are perceived as a background. (Tokyo National Museum)

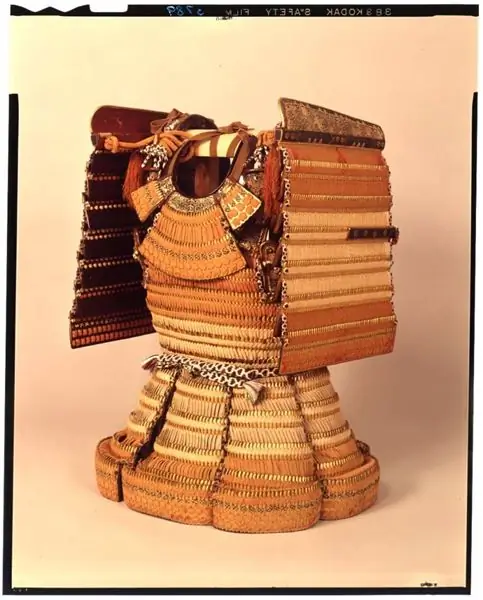

So let's start with the main difference. And it was as follows: if the European armor of the chain mail era consisted of chain mail and "metal scales", then Japanese armor at that time was assembled from plates that were connected to each other using colored cords. Further, both the Chinese and the same Europeans in armor, they all had approximately the same size. They were usually riveted to leather or fabric, both from the outside and from the inside, while the heads of the rivets protruding outward were gilded or decorated with decorative rosettes.

Japanese sword of the 5th - 6th centuries (Tokyo National Museum)

Japanese classic armor of the Heian era (like o-eroi, haramaki-do and d-maru) consisted of three types of plates - narrow with one row of holes, wider with two rows, and very wide with three. The plates with two rows of holes, called o-arame, were in the majority of the armor, and this was the main difference between the ancient armor. The plate had 13 holes: five on the top (large - kedate-no-ana) and 8 on the bottom (shita-toji-no-ana - "small holes"). When the armor was assembled, the plates were superimposed on each other in such a way that each of them would half cover the one that was on her right side. At the beginning, and then at the end of each row, one more plate was added, which had one row of holes, so that the "armor" turned out to be double thickness!

If shikime-zane plates with three rows of holes were used, then all three plates were superimposed on each other, so that in the end it gave a triple thickness! But the weight of such armor was significant, so in this case they tried to make the plates out of leather. Although the leather plates, made of durable "plantar leather", and also superimposed one on top of the other in two or three or three rows, provided very good protection, the weight of the armor is much less than that assembled from plates made of metal.

Today, quite a lot of interesting literature in English on Japanese armor is published abroad, and not only of Stephen Turnbull alone. This brochure, for example, despite the fact that it is only 30 pages, provides a comprehensive description of Japanese armor. And all because it was done by the specialists of the Royal Arsenal in Leeds.

In the 13th century, thinner kozane plates appeared, which also had 13 holes each. That is, the holes for the cords in them were the same as in the old o-arame, but they themselves became much narrower. The weight of armor made from such plates immediately decreased, because now they contained less metal than before, but the required number of plates that needed to be forged, holes made in them, and most importantly, covered with protective varnish and tied with cords, increased significantly.

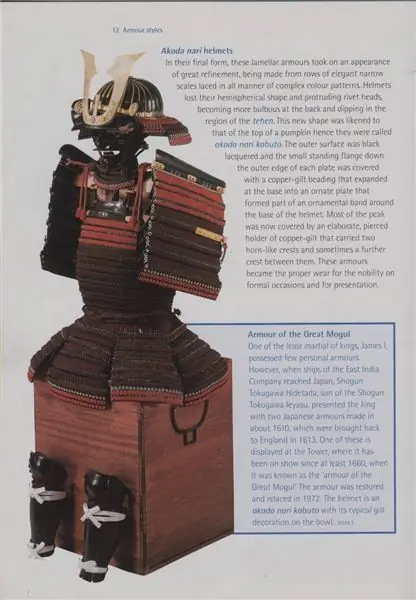

Page from this brochure. It shows the armor presented to the English King James I by the Tokugawa Shogun Hidetada in 1610.

However, the technology for assembling such armor has also been improved and somewhat simplified. If, for example, each of the plates had previously been varnished separately, now stripes were first collected from them, and only now they were varnished all at the same time. The process of making armor has accelerated, and they themselves, albeit not much, have become cheaper. Then, in the 14th century, new yozane records appeared, which were wider than the previous kozane.

Haramaki-do armor with o-yoroi shoulder pads. Momoyama era, XVI century (Tokyo National Museum)

In any case, the technology of connecting the plates with cords was very laborious, although at first glance there was nothing particularly complicated in it - sit for yourself, and pull the cords through the holes so that one plate is laced to the other. But it was a real art, which had its own name - odoshi, because it was necessary to tie the plates so that their rows did not sag and did not shift.

Reconstruction of the o-yoroi armor. (Tokyo National Museum)

Of course, sagging, as well as stretching the cords, be they made of leather or silk, was never completely avoided, since they simply could not help but stretch under the weight of the plates. Therefore, the master armors in Japan have always had a lot of work to do. They tried to increase the rigidity of the armor by lacing the yozane plates onto a leather strip. But … in any case, the skin is skin, and as soon as it got wet, it lost its rigidity, stretched, and the rows of plates diverged to the sides.

Another reconstruction of the armor of the Edo period, XVII century. (Tokyo National Museum)

The o-sode shoulder pads from this armor bear the Ashikaga clan emblem - the color of the paulownia. (Tokyo National Museum)

That is, before the meeting with the Europeans, neither chain mail nor solid-forged armor was used in Japan. But on the other hand, in the decoration of these discs, the imagination of the masters knew no bounds! But first of all, it should be noted that the plates of Japanese armor were always necessarily covered with the famous urushi varnish. Europeans cleaned their chain mail from rust in barrels of sand. Armor made of solid-forged plates was blued, gilded, silver-plated, and dyed. But the Japanese preferred varnishing to all this saving technique! It would seem, what's the big deal? I took a brush, dipped it in varnish, smeared it on, dried it and you're done! But in reality, this process was much more laborious and complex, and not everyone outside of Japan knows about this.

Breastplate with imitation plates and cords, completely covered with varnish. (Tokyo National Museum)

To begin with, collecting the sap of a lacquer tree is not at all easy, since this sap is very poisonous. Further - the varnish coating must be applied in several layers, and between each application of varnish, all surfaces of the varnished products should be thoroughly sanded with the help of emery stones, charcoal and water. All this is troublesome, but … familiar and understandable. Drying products coated with Japanese varnish is also done in a completely different way than if you used oil or nitro varnish.

The rare lacing of Japanese armor, used on later armor of the tosei gusoku type, made it possible to see the plates of the armor much better. (Tokyo National Museum)

The fact is that the urushi varnish needs dampness (!), Humidity and… coolness for complete drying! That is, if you dry products from it under the sun, nothing will come of it! In the past, Japanese craftsmen used special cabinets for drying varnished products, arranged so that water flowed along their walls, and where thus an ideal humidity of about 80-85% and a temperature of no higher than 30 ° degrees were maintained. The drying time, or it would be more correct to say - the polymerization of the varnish, was equal to 4-24 hours.

This is what the famous lacquer tree looks like in summer.

The easiest way, of course, would be to take a metal plate, paint it, say, black, red or brown, or gilded and varnished it. And often this is exactly what the Japanese did, avoiding unnecessary trouble and getting a completely acceptable result in all respects. But … the Japanese would not be Japanese if they did not try to create a textured finish on the records that would not deteriorate from impacts and would also be pleasant to the touch. To do this, in the last few layers of varnish, the master armors introduced, for example, burnt clay (because of this, even a completely wrong opinion arose, as if the plates of Japanese armor had a ceramic coating!), Sea sand, pieces of hardened varnish, gold powder, or even ordinary land. Before varnishing, the plates were painted very simply: black with soot, red with cinnabar, for brown, a mixture of red and black paints was used.

With the help of varnish, the Japanese made not only their armor, but also a lot of beautiful and useful things: screens, tables, tea trays and all kinds of boxes, well, for example, such as this "cosmetic bag" made in the Kamakura era, XIII century … (Tokyo National Museum)

"Cosmetic Bag" - "Birds", Kamakura era of the XIII century. (Tokyo National Museum)

For a greater decorative effect, after the first 2-3 varnish coatings, the craftsmen sprinkled the plates with metal sawdust, pieces of mother-of-pearl or even chopped straw, and then again varnished them in several layers, using both transparent and colored varnish. Working in this way, they produced plates with a surface imitating wrinkled leather, tree bark, the same bamboo, rusty iron (the motif, by the way, is very popular in Japan!), Etc. later Japanese armor. The reason - the spread of the cult of tea, because good tea had a rich brown color. In addition, the red-brown lacquer coating made it possible to create the look of iron corroded by rust. And the Japanese literally raved (and raved!) "Antiquity", adore old utensils, so this is not at all surprising, not to mention the fact that the rust itself was not there in principle!

Box from the Muromachi era, 16th century (Tokyo National Museum)

It is believed that this varnish in Japan became famous thanks to Prince Yamato Takeru, who killed his brother, and then the dragon, and performed many more different feats. According to legend, he accidentally broke a branch of a tree with bright red foliage. A beautiful, shiny juice flowed from the break, and for some reason the prince had the idea to order his servants to collect it and cover his favorite dishes with it. After that, she acquired a very beautiful appearance and extraordinary strength, which the prince really liked. According to another version, the prince wounded the boar while hunting, but could not finish it off. Then he broke a branch of a lacquer tree, smeared it with juice on the arrowhead - and, since the juice of this turned out to be very poisonous, he killed him.

Japanese varnish is so strong and resistant to heat that even teapots have been covered with it! Edo period, 18th century

It is not surprising that the records, finished in such an intricate manner, were indeed very beautiful and could withstand all the vagaries of the Japanese climate. But one can imagine the whole amount of labor that had to be spent to varnish several hundred (!) Of such plates, which are needed for traditional armor, not to mention tens of meters of leather or silk cords, which required joining them. Therefore, beauty is beauty, but the manufacturability, strength and reliability of armor also had to be taken into account. In addition, such armor was heavy to wear. As soon as they got into the rain, they got wet and their weight increased very much. God forbid, in wet armor, to be in the cold - the lacing was frozen and it became impossible to remove them, it was necessary to warm up by the fire. Naturally, the lacing got dirty and had to be undone and washed from time to time, and then the armor was reassembled. They also got ants, lice and fleas, which caused considerable inconvenience to the owners of the armor, that is, the high quality of the plates themselves devalued the very method of their connection!

It just so happened that I was lucky to be born in an old wooden house, where there were many old things. One of them is this Chinese lacquer box (and in China the lacquer tree also grows!), Decorated in the Chinese style - that is, with gold painting and applications of mother-of-pearl and ivory.

Trade with the Portuguese also led to the emergence of the Namban-do armor ("the armor of the southern barbarians"), which was modeled on the European ones. So, for example, hatamune-do was an ordinary European cuirass with a stiffening rib protruding in front and a traditional skirt attached to it - kusazuri. Moreover, even in this case, these armor did not shine with polished metal, like "white armor" in Europe. Most often they were covered with the same varnish - most often brown, which had both a utilitarian meaning and helped to introduce a purely foreign thing into the Japanese world of perception of form and content.

The Vietnamese adopted the skill of working with varnish, and began to make such boxes themselves, which were supplied to the USSR in the 70s of the last century. Before us is a sample of eggshell inlay. It is glued to paper, the pattern is cut out, and already it is glued to the varnish with the paper upwards. Then the paper is sanded, the product is again varnished and sanded again until the shell ceases to stand out above the main background. Then the last layer is applied and the product is ready. Such is the discreet, mean beauty.

One of the manifestations of the decline in the arms business was the revival of old styles of weapons, a trend that received significant impetus from the book of the historian Arai Hakuseki, published in 1725, Honto Gunkiko. Hakuseki adored the old styles such as the o-yoroi armor, and the blacksmiths of that time tried to reproduce them for the needs of the public, sometimes creating bizarre and incredible mixtures of old and new armor, which had no practical value. By the way, the funniest samurai armor, which even got into many museums and private collections, was made … after the end of World War II and the occupation of Japan by American troops. Then the Japanese cities lay in ruins, the factories did not work, but as life went on, the Japanese began to produce souvenirs for American soldiers and officers. These were, first of all, skillfully made models of temples, junoks and Japanese samurai armor, since the occupation authorities were forbidden to make the same swords. But do not make souvenir armor from real metal? It is necessary to forge it, and where can you get it ?! But there is as much paper around as you like - and it was from it, covered with the same famous Japanese varnish, that this armor was made. Moreover, they also assured their customers that this is a real antiquity and that they have always had it! From here, by the way, there was talk that the samurai armor was record-breaking light in weight and was made of pressed paper and bamboo plates!

Vietnamese chess inlaid with mother-of-pearl is also from that era.

However, it must be emphasized that the Japanese would never have any armor at all, neither metal nor paper, if not for … yes, yes, the natural geographic conditions in which they lived on their islands, and precisely because of which there the famous lacquer tree grew, giving them the urusi lacquer they needed! And that is why the haiku about summer was chosen as an epigraph to this chapter. After all, it is harvested only at the beginning of summer (June-July), when foliage growth is most intense …

Another box "from there" with the image of the islands of the South China Sea. A very simple and artless image, but it's nice to use this box.

By the way, it is still unclear how the ancestors of today's Japanese came up with the idea of using the sap of lacquer wood as a varnish. What helped them in this? Natural observation? Lucky case? Who knows? But be that as it may, it is to this varnish that Japan owes the fact that many of the armor made by its masters have survived to this day, despite all the vicissitudes of its climate, and even today delight our eyes.